As I started researching smaller class sizes, my Google search made it evident that smaller class sizes are significantly better … for students in private schools. Private schools use small class sizes to sell their product. They also get to pick who will be in their classes and who will be in their schools.

With campuses in New York, Oxford, and Torbay, the EF Academy of international boarding schools cites the key features of optimum class sizes of 17 students as “each student gets noticed”, students have “higher grades” and “perform better”, “learning is enhanced”, “teachers can teach”, “classes become a community”, “small groups mean fewer voices” so students have “more chances to speak”, teachers can focus on learning and spend less time dealing with distracted students, teachers can give more “individualized feedback”, teachers can work “on-on-one”, and “ideas are shared”.

Based on my own 19 years of teaching grades 2 through to grade 8, I know that even with large class sizes up to 30 students, I’ve been able to provide individualized feedback and present all students opportunities to speak, share ideas, and to participate in the classroom. I did not have students with significant learning or behaviour issues. I was also supported by a special education teacher on a daily basis. My classroom ran smoothly most of the time but a lot depended on who was in my classroom.

Class Size Really Matters to Students with Special Education Needs

One big impact in teaching larger class sizes is for the work teachers need to do to differentiate instruction and assessment to meet students’ needs. This is especially relevant in supporting students with special education needs. Students with special education needs may not be learning at their age appropriate grade level, may have Individual Education Plans, and may have very specific emotional needs.

Over the last 19 years, I’ve taught students functioning at three grade levels below their peers. In this case, teachers must adapt or modify students’ work as these instructional needs are prescribed in students’ Individual Education Plans. When teaching students with specific individual learning needs, teachers cannot simply plan, instruct, and assess with the “one-size-fits-all” approach. Teaching students with varying learning needs requires a great deal of work, thus teachers need a nimble knowledge of instruction and pedagogy. In addition, some students may be functioning at their grade level in a subject like math but need accommodations and modifications for subjects dealing with subjects like language. This adds to the complexity of teaching.

Class Composition Matters

Another aspect of class size is class composition. This means that one class of 23 grade 6 students is not the same as another class of 23 grade 6 students. I’ve taught some classes where most students were functioning at grade level, however several students had significant issues that impacted their academic achievement and/or behaviour. Recently, from anecdotal evidence, I’ve noted a significant increase in classroom compositions of students with additional learning and behavioural needs. I’ve spoken to colleagues with class compositions where almost half of the students had special education and/or behavioural needs – these teachers dealt with these classes with little or no additional support.

In my own 11 years of middle school, I’ve taught mainstream middle school classrooms of students with multiple needs. These issues included autism, attention deficit disorders, anxiety disorders, oppositional defiant disorders, depression, eating disorders, and self-harming disorders (i.e. cutting). In addition, many students had learning disabilities that co-occured in complexity which made it tough to support the students in their learning. I’ve taught students with a myriad of learning disabilities which included dyslexia (i.e. reading challenges), dysgraphia (i.e. writing challenges), and dyscalculia (i.e. math challenges), dyspraxia (i.e. motor skill challenges), aphasia/dysphasia (i.e. language impairment), auditory processing disorder (i.e. difficulty processing sound), and memory issues. Further, teachers must deal with students who have social and emotional issues due to learning challenges, familiar issues, and/or socioeconomic issues. When considering the intersectionality of students’ needs, it can be overwhelming for a teacher to take on even one more student.

Smaller Class Sizes Cost Money

Smaller class sizes results in teachers having more time to spend with students. Smaller class sizes also means that with fewer students, there are less chances of disruptions interfering with learning. Smaller class sizes allows teachers to direct their energy to the business of learning and not the task of managing behaviour.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (2018) the pupils per teacher ratio “declined from 22.3 in 1970 to 17.9 in 1985 … the ratio declined from 17.3 in 1995 to 15.3 in 2008.” After the 2008 recession, the public school pupil/teacher ratio increased, reaching 16.1. In 2014, private schools (who select students) had class sizes of 12.2 pupils (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). In 2011-2012, average class size was “21.2 pupils for public elementary schools and 26.8 pupils for public secondary schools” (National Center for Education Statistics, 2018). Note that these class sizes are significantly smaller than Ontario’s current numbers, and still Ontario leads in solid data showing student success.

In 2003, Allan Krueger of Princeton University and Eric Hanuskek of Stanford University’s Hoover Institution debated the merits of class size (edited by Mishel & Rothstein, 2002). Krueger’s stance maintained that smaller class sizes improved students’ performance and future earning prospects. Hanuskek argued that reduced class size was only one aspect of student success and that improving teacher quality made a significant impact on students’ performance. As in most aspects of education, the educational landscape is complex and does not respond to single-issue solutions.

Lazear (1999) highlighted the link between smaller class sizes as this “reduces a student’s propensity to disrupt subsequent classes because the student learns to behave better with closer supervision, or enables teachers to better tailor instruction to individual students” (Krueger, 2003, p. 23). Lazear (1999) indicated that the “optimal class size is larger for groups of students who are well behaved, because these students are less likely to disrupt the class” (Krueger, 2003, p. 23). Lazear further stressed that “if schools behave optimally, they would reduce class size to the point at which the benefit of further reductions are just equal to their cost. That is, on the margin, the benefits of reducing class size should equal the cost” (Krueger, 2003, p. 23-24). In other words, when students’ behaviour is optimal, larger class sizes can be as effective as smaller class sizes.

The big challenge with most research on class size is that it does not provide definitive numbers specifying benchmarks on the class size (i.e. number of students) to which they are referring (Filges, Sonne-Schmidt, & Nielsen, 2018).

By referring to the numbers published by the National Center for Education Studies (2018), 21.2 students per class in public elementary schools and 26.2 students per class in secondary schools can be used as a current reference. With recent changes to the Ontario public school system, having more than 25 students in grade 1 to 8 classrooms is 18% over the average for public schools in the United States. Further, having 28 students in secondary classes is 7 % over the average for public schools in the United States. Note that these are averages and do not take into account variables in class sizes for types of class and subject taught.

Living in the Real World of the Classroom

As a full time classroom teacher, I have the benefit of sifting through the literature and then putting it through the “real life classroom lens.”

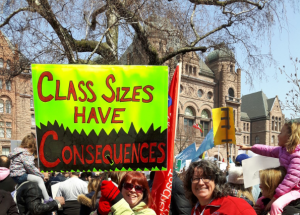

When I was a grade 5 student in elementary school, classrooms were significantly different than they are today. We sat in rows and we did our work – there was no collaboration with other students and certainly no talking during class. Thus disruptions were minimal. I had 32 kids in my class (see the picture above – 3 kids were absent). Students who were not successful failed. Students who were deemed “special” and not at grade level were not integrated into our classroom – they were in the special classes.

As a classroom teacher, I have taught 33 students in a grade 8 classroom that could barely seat all the students – during the school year the students literally grew out of their desks. With 21st century learning, classrooms have become flexible in their seating and have pushed for a focus onto collaborative learning. Students get more say in how they are taught and assessed through co-created success criteria and self and peer assessment. This is a positive step as it makes students part of the learning and they are more engaged in the learning.

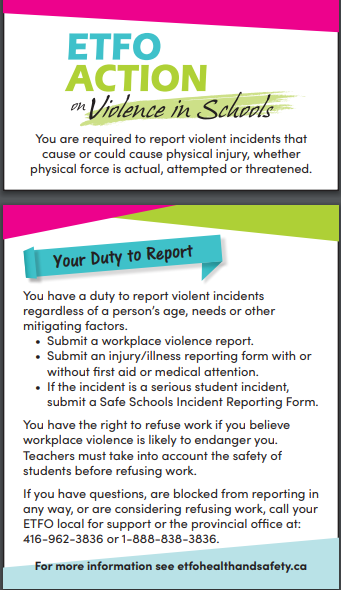

Recent research has shown that student behaviour continues to decline. There is much research documenting increases in student violence in schools. In an ETFO sponsored study it was reported that over 70% of Ontario elementary educators surveyed had seen or experienced classroom violence. A Canada-wide study conducted by the Canadian Teachers’ Federation (CTF) showed that at least four in 10 teachers experienced violence from students. I personally have been bitten, kicked, pushed, and had objects thrown at me by students. Students are experiencing significant behaviour challenges that go beyond being dealt with using standard classroom management strategies. To add to this, students’ instructional and assessment needs continue to grow, increasing the need for more special education support.

Larger class sizes not only challenge teachers, they also result in students with academic and emotional needs not being able to participate in their classroom. This results in frustration and sometimes behavioural challenges. With smaller class sizes, teachers can support students more fulsomely to help them with their learning needs and reduce behavioural challenges.

If the provincial government wants to increase class sizes, our provincial leaders need to first support teachers in dealing with student behaviour and to increase funding for special education needs. As Lazear stated in his research, when students are well behaved, larger class sizes are effective. Until this happens, class sizes should remain as is or even get smaller, as student behaviour is becoming untenable.

Collaboratively Yours,

Dr. Deborah Weston, PhD

References

Canadian Teachers Federation (Jul 09, 2018). Lack of resources and supports for students among key factors behind increased rates of violence towards teachers Downloaded from https://www.newswire.ca/news-releases/lack-of-resources-and-supports-for-students-among-key-factors-behind-increased-rates-of-violence-towards-teachers-687675241.html

Filges, T., Sonne-Schmidt, C. S., & Nielsen, B. C. V. (2018). Small Class Sizes for Improving Student Achievement in Primary and Secondary Schools: A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 2018: 10. Campbell

Krueger, A. B. (2003). Economic considerations and class size. The Economic Journal, 113(485), F34-F63. Downloaded from https://www.nber.org/papers/w8875.pdf

Lazear, E. P. (1999). ‘Educational Production.’ NBER Working Paper No. 7349, Cambridge, MA.

Mishel, L., & Rothstein, R. (2002). The class size debate (p. 3). A. B. Krueger, E. A. Hanushek, & J. K. Rice (Eds.). Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. http://borrellid64.com/images/The_Class_Size_Debate.pdf

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2018). Digest of Education Statistics, 2016 (NCES 2017-094), Introduction and Chapter 2. Downloaded from https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=28