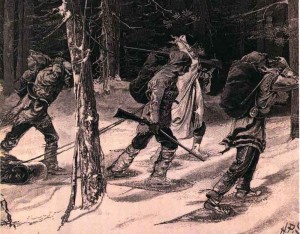

If you have studied Canadian History, you will know that without the establishment of the fur trade, our nation of Canada may have been limited to the banks of Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, the Saint Lawrence River, and the Atlantic Ocean. Without the push of fur traders called Courier du Bois (i.e. Runners of the Woods) and their exploration carving out routes through forests, creeks, lakes, and rivers, Canada may have not been established in the west as it is today.

We know that European and Aboriginal men traveled through these routes transporting large quantities of fur, particularly Beaver fur. The men lived in harsh climates, especially in the  winter. The European men came to North American accustomed to a different less harsh weather, and faced dealing with different food sources and clothing unsuitable for the Canadian climate.

winter. The European men came to North American accustomed to a different less harsh weather, and faced dealing with different food sources and clothing unsuitable for the Canadian climate.

So how did these men survive and who provided the clothing and food needed to face a very different climate?

The answer is evident but not obvious to Canadians … it was the First Nations women who played a vital role in establishing Canada’s fur trade. It was First Nations women who provided travelers and fur traders with the tools they needed to explore Canada.

What tools did the First Nations Women provide?

Knowledge of the Land:

First nations women acted as guides and interpreters for fur trading as they knew the languages and trading customs of many First Nations groups. These women guided Europeans through well established aboriginal trails and trading routes and along Canada’s lakes and rivers. These women knew the best places to camp and how to set up a campsite with fires, meals, and comfortable bedding.

Food for Survival:

First Nations women knew which plants and animals could be eaten. Picking the wrong, leaves, roots, shoots, fruits, and berries to eat could result in sickness or worse, death!

Picking the right food could result in delicious, nourishing meals which provided enough calories to fuel long trips through the wilderness. These women taught Europeans how to fish and trap animals for food as well as preserve food for winter. They taught the Europeans how to plant corn and use it for bread, like bannock or corn stew like sagamit. The First Nations women provided fur traders with high calorie Pemmican made from dried bison, moose, caribou, or venison meat powder mixed with animal fat and berries (see recipe below). Apparently Pemmican can last over 50 years without going bad, now that’s the ultimate survival food!

Picking the right food could result in delicious, nourishing meals which provided enough calories to fuel long trips through the wilderness. These women taught Europeans how to fish and trap animals for food as well as preserve food for winter. They taught the Europeans how to plant corn and use it for bread, like bannock or corn stew like sagamit. The First Nations women provided fur traders with high calorie Pemmican made from dried bison, moose, caribou, or venison meat powder mixed with animal fat and berries (see recipe below). Apparently Pemmican can last over 50 years without going bad, now that’s the ultimate survival food!

Preparing Furs for Trade:

The First Nations women knew how to trap the animals to get the best fur for trade. Once caught, animal furs needed to be prepared for sale. Preparing furs for trade meant work. Furs had to be cleaned through scraping, strung and stretched while drying, and tanned so they did not rot. Well prepared furs sold for high prices.

Making Clothing for the Climate:

From the skins and furs, First Nations women made clothing perfect for the Canadian climate. They sewed moccasins, coats, mittens, and leggings to keep traders protected from the elements. They also wove blankets and used furs and skins to make shelters and bedding.

And with the addition to these tools, First Nations women provided the future of Canada with the most important resource, people. First Nations women had common-law marriages with European men who’s union produced a great many generations of hardy future Canadians, ready to survive and thrive in Canada’s northern climate.

In Fort Albany, in James Bay, Robert Goodwin (1761 – 1805) from Yoxford, England, a Hudson Bay Company surgeon, had “a la facon du pays” or a country common-law marriage with Cree Woman Mistigoose (1760-1797), a Goose Cree woman probably from the Lake Nipigon area. Their first child was Caroline Goodwin (1783-1832). Robert also took on a second Goose Cree wife, possibly a sister or close relatives of Cree Woman’s, called Jenny Mistigoose (1765-1864), daughter of Pukethewanisk. Both these First Nations women likely provided Robert with the supplies, food, and clothing he needed to do his work dealing with broken bones, cuts, infection, consumption (TB), scurvy, smallpox, malnutrition, frost bite, gangrene, gout, and STDs. In 1797, when Robert Goodwin took his son, William Adolphus Barmby Goodwin to England to get an education (and live with his lawyer), William’s Cree mother, Jenny drowned herself from grief in the bay of Fort Albany. In this death in his 45th year, Robert included the support and ongoing care of his wives and over 8 children in his will.

At around the same time, John Hodgson (1764-1833) from St Margaret’s, Westminster, London, was Hudson Bay Company’s Fort Albany Chief Factor (between 1800 & 1810). John Hodgson had a country marriage with Ann, a Cree Woman, possibly from Thunder Bay. Their union produced a first born son, James Hodgson (1782-1826) also know as James Hudson. Ann supported her husband by providing him with food, shelter, and clothing to sustain him in his work and at the same time gave birth to over 12 children.

Caroline Goodwin married James Hudson and had over 16+ children together.

Goodwin married James Hudson and had over 16+ children together.

Their 7th child was Mary Ann Hudson, granddaughter to Robert Goodwin, Cree Woman (wife #1) Mistigoose, John Hodgson, and Ann Mistigoose.

Mary Ann Hudson was also my third great grandmother (discovered in 2017).

So, not only were the First Nations women important to the support and expansion of Canada’s fur trade, these women also helped establish the population of our future Canada. Today, like me, Canadians are here because they have, knowingly or unknowingly, First Nations, Métis, and Inuit ancestry.

So when Rosanna Deerchild on CBC Radio welcomes listeners as “your favourite cousin”, indeed, some Canadians may truly be all cousins.

Next time you look at a Beaver on the Canadian nickel … remember who did all the work to make the fur trade a success in Canada.

Collaboratively Yours,

Deb Weston

PS: Unfortunately, none of the people in these pictures are related to me.

How To Make Pemmican

We recommend trying HQ’s recipe as stated above, but if you’re looking for more precise instructions, we found this pemmican recipe by the University of Minnesota. This recipe makes 3.5 lbs. http://www.alloutdoor.com/2014/01/28/this-pemmican/

Ingredients:

- 4 cups dried meat (only deer, moose, caribou, or beef)

- 3 cups dried fruit (currents, dates, apricots, or apples)

- 2 cups rendered fat (only beef fat)

- 1 cup unsalted nuts (optional)

- 1 tbsp of honey (optional)

Supplies:

- Cookie sheet

- Mortar and pestle

- Kitchen knife

Instructions:

First, dry the meat by spreading it thinly on a cookie sheet. Dry at 180° overnight, or until crispy and sinewy.

With the mortar and pestle, grind the dried meat into a powder.

Add the dried fruit and grind accordingly, leaving some larger fruit chunks to help bind the mixture.

Cut the beef fat into chunks.

Heat the stove to medium, and cook the beef until it turns to tallow (rendered fat).

Stir the fat into the powdered meat and fruit mixture.

Add nuts and honey to improve taste (optional)

Shape pemmican into balls or bars for easy and quick consumption. We recommend wrapping individual servings in wax paper or storing in plastic bags.

References

Rosanna Deerchild

http://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/rosanna-deerchild-1.2813088

Robert Goodwin

https://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/hbca/biographical/g/goodwin_robert.pdf

http://www.metismuseum.ca/media/document.php/07205.Notes%20on%20Robert%20Goodwin.pdf

John Hudgson

https://www.gov.mb.ca/chc/archives/hbca/biographical/h/hodgson_john.pdf

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/hodgson_john_6E.html

“She is Particularly Useful to Her Husband”: Strategic Marriages Between Hudson’s Bay Company Employees and Native Women – https://www.nps.gov/articles/hbcmarriages.htm

winter. The European men came to North American accustomed to a different less harsh weather, and faced dealing with different food sources and clothing unsuitable for the Canadian climate.

winter. The European men came to North American accustomed to a different less harsh weather, and faced dealing with different food sources and clothing unsuitable for the Canadian climate.

Picking the right food could result in delicious, nourishing meals which provided enough calories to fuel long trips through the wilderness. These women taught Europeans how to fish and trap animals for food as well as preserve food for winter. They taught the Europeans how to plant corn and use it for bread, like bannock or corn stew like sagamit. The First Nations women provided fur traders with high calorie Pemmican made from dried bison, moose, caribou, or venison meat powder mixed with animal fat and berries (see recipe below). Apparently Pemmican can last over 50 years without going bad, now that’s the ultimate survival food!

Picking the right food could result in delicious, nourishing meals which provided enough calories to fuel long trips through the wilderness. These women taught Europeans how to fish and trap animals for food as well as preserve food for winter. They taught the Europeans how to plant corn and use it for bread, like bannock or corn stew like sagamit. The First Nations women provided fur traders with high calorie Pemmican made from dried bison, moose, caribou, or venison meat powder mixed with animal fat and berries (see recipe below). Apparently Pemmican can last over 50 years without going bad, now that’s the ultimate survival food!

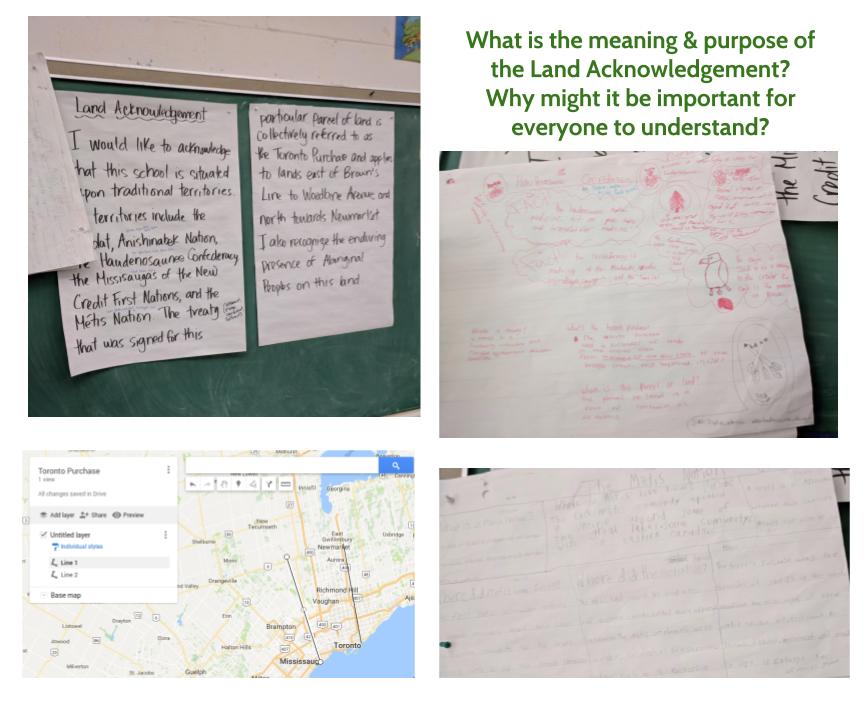

In my class this year, I’ve made it a goal to ensure that Indigenous perspectives are reflected in both my teaching and in our learning space. In the past I’ve struggled with months or days to celebrate a particular heritage or cultural group because I find that it leads to tokenism. While there is value in that celebration, I wonder how we might be able to go beyond and infuse this learning into our everyday experiences with students. I’m learning the importance of valuing inquiry as students start to investigate for themselves diverse experiences within Canada. Earlier this year, we read

In my class this year, I’ve made it a goal to ensure that Indigenous perspectives are reflected in both my teaching and in our learning space. In the past I’ve struggled with months or days to celebrate a particular heritage or cultural group because I find that it leads to tokenism. While there is value in that celebration, I wonder how we might be able to go beyond and infuse this learning into our everyday experiences with students. I’m learning the importance of valuing inquiry as students start to investigate for themselves diverse experiences within Canada. Earlier this year, we read