Education policy implementation is a complex process that requires the input of all stakeholders including teachers, school staff, parents, and school communities. As major players in policy implementation, teachers decode and recode policy texts in the process of understanding and translating with various degrees of intentional and unintentional interpretation (Clune, 1987; Fuhrman, Clune, & Elmore, 1991).

In the complex process of policy implementation, teachers experience challenges with implementing educational reforms where previous policy initiatives have not met their objectives (Fullan, 2001). In the layers of educational initiatives, an “array of policies” implemented simultaneously in schools, can cause policy overload within teachers’ practices (Fullan & Hargreaves, 1996; Grossman & Thompson, 2004).

In addition, teachers’ thinking is focused on the complexities and ambiguity of their classroom practice and not necessarily on system-wide views of initiative implementation (Timperley & Robinson, 2000). This means that policies, developed with the system-wide perspective of policy authors, may conflict with the classroom-bound perspectives of teachers.

Teachers’ reactions to the “fragmented and cluttered” policy implementation process may be viewed as teachers being resistant to change. This instead may be a response to the accumulation of past policy experiences, policy overload, policy fragmentation, policy contradictions, and competing perspectives (Timperley & Robinson, 2000). In other words, most education policies don’t fit into the complex and variable context of teachers’ classrooms.

Even when educational policies do not present the intended results, policy authors still believe the design of their policies is an effective way to make change in education. Greenfield (1993) argues that although this reality “usually fails to shake our faith in such theory” (p. 3), it implies that “we need to ask whether the theory and assumptions still appear to hold in the settings where they were developed before they are recommended and applied to totally new settings” (p. 4).

In other words, are education policies producing the intended results in all schools and classrooms? Policy authors rarely follow up with an audit of the effectiveness of their policies nor do they consider if their policies have resulted in harmful consequences to schools, to school communities, and to students’ lives. This is particularly objectionable when the health and lives of students and teachers is impacted.

What makes good policy implementation?

(Viennet & Pont, 2017)

Smart policy design:

Well developed policies offer a logical and feasible solutions to policy problems. Effective policy implementation is based on the feasibility of adequate resources available to support its successful implementation. These resources should include funding to ensure adequate staffing and supplies to support policy implementation in schools that support the policy’s framework.

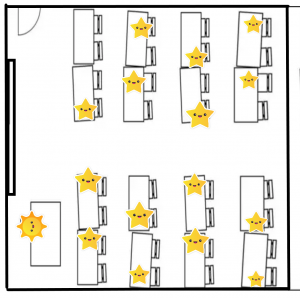

For example, if a policy is framed upon students being able to social distance in classrooms, then there should be enough space in classrooms to accommodate students with this level of distancing. If classrooms are not large enough to have over 25 students sitting in desks spread out over the classroom, the policy is sure to fail.

Including stakeholders like educators:

Whether and how key stakeholders (i.e. educators, parents, communities, students) are recognized and included in the implementation process is crucial to any policy’s effectiveness. Without the input of front-line stakeholders, the intended policy objectives could result in unintended consequences.

For example, if a policy is to be implemented in the landscape of schools and classrooms in communities, it is imperative that those with intimate knowledge of the landscape should be consulted in order to unearth any obvious challenges presented. An example of this is the diversity of classroom layouts and its contents. Classrooms are as unique as the people who learn in them. Not all classrooms are the same size or configuration. Further, not all classrooms contain desks and instead have collaborative work areas where students sit at tables. If students are to sit two metres or even one metre away from each other, tables may only have one spot for a student. If a policy is based on a configuration of desk placements, it will fail unless furniture is purchased to meet the policy’s assumptions.

Policy designed for schools and their communities:

An effective policy implementation process recognizes the existing policy environment (i.e. schools before Covid-19), the educational governance (i.e. board and school administration) and institutional settings (i.e. elementary and secondary schools) and the external context (i.e. returning to school in a pandemic). Without input from frontline stakeholders, policy authors may produce policy recommendations that are completely inappropriate for schools and their communities.

For example, implementing a return to school policy based on schools’ past configurations will likely result in a quick realization that this assumption is flawed. The practical conclusion is that there will be no way to fit the same number of students into the same amount of space with the implementation of a social distancing policy.

Sensible policy strategies for schools:

A coherent implementation takes into consideration all the guidelines and resources needed to make a policy operational at the school level (i.e. policy needs to be flexible enough to meet the needs of schools’ in their particular communities).

For example, policy authors may mandate synchronous daily online learning sessions for each classroom. Policy makers may not consider the specific technology and the resultant cost for the set up of these online sessions. One most obvious challenge is that there might not be enough Internet bandwidth to support the synchronous daily learning sessions simultaneously for all classes in all schools in Ontario at the same time. In June of 2020, I personally had my own class synchronous learning sessions crash when my board’s staff meetings were occurring at the same time.

Safe Schools in September?

In summary, without consulting school staff and their communities, policy authors will likely see their policy objectives fail as they did not consider the context in which their policies were to be implemented. On a further note, as school boards are already stretched for funding, no additional funding will result in policy implementation that is not smart and not implemented.

I write this blog in a state of frustration and concern as Ontario’s Ministry of Education released plans to open schools in September 2020. Key stakeholders were not consulted in the making of this policy which have resulted in glaring deficits in it’s implementation, particularly in elementary schools.

As a person who has taught through 20 years of education policy implementation, I know education policies fail more than they succeed. I’ve worked through half-baked policy implementation that was only partly implemented or completely abandoned. I’ve faced the fall out of failed policies such as having hand sanitizer in schools during the H1N1 outbreak as some students became sick from ingesting this substance.

Even the thought of having to manage the social distancing of so many students makes my head spin.

My greatest fear is that school communities will face outbreaks of Covid-19 and people will get very sick. The worse negative consequence is that school communities may have to mourn the loss of a person belonging to their community.

A failed return to school policy may end up failing us all.

Take care of yourself and your communities.

Stay safe.

Deb Weston, PhD – a concerned classroom teacher

PhD in Education Policy and Leadership

References

Clune, W. H. (1987). Institutional choice as a theoretical framework for research on educational policy. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 9(2), 117-132.

Fuhrman, S., Clune, W., & Elmore, R. (1991). Research on education reform: Lessons on the implementation of policy (pp. 197-218). AR Odden, Education Policy Implementation. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Fullan, M. (2001). The new meaning of educational change (3rd ed.). Toronto, ON: Irwin.

Fullan, M., & Hargreaves, A. (1996). What’s worth fighting for in your school? New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Greenfield, T. (1993). Theory about organization: A new perspective and its implications for schools. In T. Greenfield & P. Ribbins (Eds.), Greenfield on educational administration (pp. 1-25), London, UK: Routledge.

Grossman, P., & Thompson, C. (2004). District policy and beginning teachers: A lens on teacher learning. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, (26)4, 281-301.

Timperley, H., & Robinson, V. (2000). Workload and the professional culture of teachers. Educational Management & Administration, 28(1), p. 47-62.

Viennet, R., & Pont, B. (2017). Education Policy Implementation: A Literature Review and Proposed Framework. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 162. OECD Publishing.

One thought on “School re-opening smart policy design: How Ontario’s current school reopening policy is not so smart”