As both a teacher and a parent, I get to see what engages children including my own. Lately, my daughter has been bursting through the door with this excitement, arms waving, cheeks flushed, words tumbling out faster than I can catch them.

And every time, her stories follow this simple but exciting pattern. A picture book they read in class. The outdoor adventure that connected to it and the research they did afterwards to answer the many questions they came up with.

Watching her connect all those pieces has reminded me, more clearly than ever, how powerful picture books and outdoor time truly are.

My daughter will start by telling me about the picture book of the day. Maybe something about forest animals or changing seasons. But it’s really what comes after the story that shows the power of those pages. She talks about the characters, the setting, and the questions the book planted in her mind.

As a teacher, I know picture books can spark inquiry.

As a parent, I get to see that spark ignite in my own child.

Then comes the outdoor stories. Her absolute favourite part.

Her class has been exploring the forested trails behind the school, and hearing her describe it feels like listening to a nature documentary narrated by a very excited five-year-old. She tells me about following the path, spotting tracks in the mud, and crouching down to look closely at “real evidence,” as she calls it.

Recently she came home thrilled about finding animal scat on the trail . “We found ‘clues’, Mom!” and she continued to explain the different lines pressed into the dirt and snow that a muskrat had dragged cattails and sticks to the pond. She explained it like she had been on a wildlife expedition. And honestly? Her excitement was contagious.

After their walk, she said they went back inside and looked up muskrats on Google, because, of course, she had a hundred questions. And the facts she learned came flying at me as soon as she got in the car. She told me these things with such joy that I couldn’t help but smile. The book gave her the curiosity, the forest gave her the evidence, and the research gave her the answers. That combination of story + exploration + information is what made the learning so powerful.

Watching her experience all of this has reminded me, both as a teacher and a parent, that these simple ingredients aren’t extras, they are the driving force for deep, joyful learning.

We don’t need elaborate materials or hours of planning. Sometimes all it takes is a story, a walk through the trees, and the chance to follow a question wherever it leads.

When my daughter comes home overflowing with enthusiasm, talking about trails, animal scat, muskrat homes, and underwater facts, it’s impossible not to see the magic. It is clear that picture books and outdoor time don’t just teach. They invite curiosity and make learning come alive.

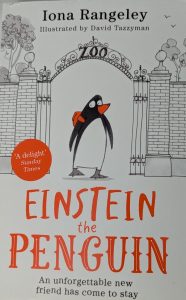

Primary Novel to Read Aloud: Einstein the Penguin by Iona Rangeley

On a family visit to the zoo the Stewart children, Imogen and Arthur, catch the eye of a small penguin. He seems to be trying to communicate with the children. As they prepare to leave, their mother says “And you, Mr. Penguin, you must come and stay with us whenever you like.” No one expects that he would soon arrive on their doorstep!

The themes of family, friendship, welcoming strangers, and helping friends are built into this tale of mystery and adventure. Einstein is a brilliant penguin who enjoys messy meals and sneaking into Arthur’s backpack to spend time at school. There are many humorous scenes as their beloved feathered friend gets into a bit of mischief trying to find his friend. We see the siblings form a tighter bond and they begin to show each other more respect as the story goes on. Both of them feel they don’t fit in but Einstein helps them have more confidence.

The story is set in during early winter so a read aloud in December or January would be very relatable. That said, it really could be read at any time of the year. In the end, the children in the story grapple with the idea of saying goodbye but they realize Einstein isn’t suited to living in a townhouse.

I love that the chapters are short enough that you just need 10-15 minutes to read each one aloud. Perfect for transitions from recess or at a time when the students have been out of the room for another subject. I remember my grade 2 teacher often read at the end of the day and we gathered together on the carpet. There is something about coming together for a read aloud that builds community as we share laughter, curiosity, fear, and sometimes even tears. No tears for Einstein though, just giggles and surprises!

Einstein the Penguin can ignite our own excitement about writing and telling stories. What type of animal could students imagine arriving at their door? Would the animal stay at their house? What kind of adventure would they have?

Learning about penguins is a natural extension of this story. There are a few varieties of penguins mentioned in the book and students will be curious to learn about them. Einstein is a little penguin (also known as fairy penguins) and his friend Isaac is a rockhopper penguin like the one voiced by Robin Williams in the animated film, Happy Feet.

Einstein the Penguin has a mystery to solve and a villain in pursuit. Your students could very well get hooked on mystery stories at a young age. Setting up a mystery in the classroom makes for a very exciting hook in a lesson plan. Something as simple as a scavenger hunt can be a time for students to show teamwork and leadership.

Students could also compare Einstein to Tacky the Penguin. As you may know Tacky is my favourite read aloud for primary grades so I wrote this blog all about it. Einstein and Tacky have similar traits of being dedicated friends and free-spirited creative thinkers. I think your students will love them both.

Happy Reading!

Brenda

Einstein the Penguin was written by Iona Rangeley and illustrated by David Tazzyman. It was published in 2021 by Harper Collins.

Strategies and Best Practices for Building Transparency and Parent Communication in ESL/ELD Programming – Part 2

In part 1 of this article, I talked about the difficulties I had faced when it came to sharing information about ESL/ELD programming with families. In the community where I worked, ESL/ELD programming was often viewed from a deficit perspective by many caregivers and even some school staff. Widely held deficit perspectives about ELLs, combined with my own need to learn more about ESL/ELD programming, resulted in rather poor communication with MLL families.

In my current work as an instructional leader working in ESL/ELD programming, I talk to educators that experience similar issues regularly. How should teachers go about addressing ESL/ELD programming with families that may not be aware of what it is? How should educators re-start conversations about their child’s ESL/ELD programming with families when it has gone unaddressed for an extended period of time?

Recently I spoke to a middle school colleague about how she communicates with MLL families when they transition to grade 6 from the feeder elementary school. Her practice was to call all MLL families to welcome them in the early months of the school year, and share with them that their child would be receiving ESL or ELD support. In her experience, families were often happy to hear how their child would be supported in this way.

The teacher also shared with me that she also calls families when their child is no longer receiving program adaptations, or had completed STEP 6 of the ESL continua. In her experience, caregivers often responded positively; after all, becoming proficient in another language is something to celebrate.

Listening to these reflections on family communication and transparency made me think of how empowered we are as educators to shift thinking in our schools and communities.

Let’s take a look at some ways educators can build transparency and communication with families about ESL/ELD programming, while also re-casting the work we do as MLL educators through an assets-based perspective.

Make Information about ESL/ELD programming Readily Available to Families

In an age of endless information, there is no reason families should have difficulty accessing information about ESL/ELD programming. Leave an easy-to-read brochure that explains what ESL/ELD programming looks like in your school in the main office so families can build their understanding and know who to contact should they have any questions.

Make ESL/ELD Programming part of Regular Family Communication

When you make welcome calls or share updates to families of MLLs, take the time to reference the student’s growth in language and literacy. It’s a great opportunity to share what you are doing to support their growth as multilingual learners, and keep the conversation going about academic language development.

Leverage Curriculum Night, Open House, and other school Community Events to Raise Awareness about ESL/ELD Programs

The tools, terminology and resources we reference as educators, like the STEP Continua, accommodations, and modifications, may be unfamiliar to families. Have a short presentation ready that you can use (or share with staff) to explain to families what these terms and tools are, and how educators use them to enhance and adjust programming for newcomer students. If possible, invite a settlement worker or community member that speaks the same language(s) as the communities in your school in to help interpret whenever necessary.

Sharing information with families about ESL/ELD programming should never feel like a hard or difficult conversation. With the right combination of direct communication and use of digital information, you will find that it will get increasingly easier to make programming for MLLs a regular part of your communication with families.

Foundations of Literacy Part II: Teaching Conjunctions

In my previous post, I shared that I implemented a foundations of literacy component to my language program to support students in developing the knowledge and skills that the revised Grades 1 – 8 Language curriculum (2023) states they need to learn to become confident, competent writers and readers. In my previous post, I also focused on how I’m explicitly teaching students sentence structures that includes sentence types and sentence forms, and I provided a brief overview of a lesson I taught. In this post, I’ll share additional strategies and insights to how I’m further supporting students in developing their ability to comprehend and compose a variety of sentence forms by teaching them about conjunctions.

Specific expectation B3.2 which focuses on grammar states that students need to demonstrate an understanding of the parts of speech, their function in a sentence and use that knowledge to support understanding and practicing expressive and receptive communication clearly.

Conjunctions are one of the nine parts of speech listed in expectation B3.2 and they are a defining component of compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences because they connect the clauses within the sentence. For example, in a compound sentence students need to understand that a coordinating conjunction can be used to connect the two or more independent clauses contained within the sentence. In a complex sentence, they need to understand that a subordinating conjunction connects an independent clause with one or more dependent clauses contained within the sentence. In a compound-complex sentence they need to understand that the sentence includes both coordinating and subordinating conjunctions that connect two independent clauses with one or more dependent clause or clauses contained within the sentence. They also need to know that some coordinating conjunctions include for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so while some subordinating conjunctions include when, if, although, before, after, since, even though, unless.

I think the value of teaching conjunctions in relation to sentence forms is that this approach helps students to deepen their understanding of one of the nine parts of speech in practice, while also supporting them in further developing their vocabulary knowledge and their ability to communicate and understand increasingly complex thoughts and ideas in written form.

Next, I’ll share a lesson and strategies I’ve used when explicitly teaching conjunctions in relation to sentence forms while working with students in intermediate grades 7 and 8. I’ll end this post with an insight I gained from my teaching experience that may be useful to other educators.

As usual practice, I began my lessons by sharing a learning goal and success criteria with students to inform them of what they were learning, why they were learning it, and how they would know when they had been successful in their learning. A sample learning goal I shared with students while explicitly teaching conjunctions was, I am practicing writing compound sentences using coordinating conjunctions and the new vocabulary I am learning to apply my understanding of both in written form. The success criteria I used to accompany this learning goal was, I can create a compound sentence using a coordinating conjunction and one of my new vocabulary words. I then provided additional insight to the learning goal and success criteria by informing students that they were learning to include and connect multiple thoughts within a single sentence using conjunctions.

I then shared a list of coordinating conjunctions along with an acronym to help students retain the information. The acronym I shared was FANBOYS – for, and, nor, but, or yet, so. After reviewing the acronym, I provided insight to how each conjunction works within a sentence by telling students a meaning associated with the conjunction; I did this to support building students’ vocabulary knowledge. For example, I shared that the conjunction for can show a reason that an action occurred within a sentence. And can provides additional information within a sentence, while but and yet can show contrast within a sentence.

Next, I provided an example of each conjunction in use within a sentence then examined the way that the conjunction connected the two independent clauses within a single sentence. My purpose for doing this work was to help students develop the background knowledge I believed they needed to successfully construct compound and later compound-complex sentences.

Following the review of the sample sentences, I modeled creating compound sentences using the coordinating conjunctions for, and, nor. Then I invited students to co-construct compound sentences using the coordinating conjunctions but, or, yet, so. I concluded the lesson by having students work in groups of 2 – 4 to create 7 compound sentences using one the coordinating conjunctions found in the FANBOYS acronym. I used this as a consolidation activity to see how well students were able construct compound sentences at the conclusion of our initial lesson.

I recently completed my second foundations of literacy assessment. Again, to monitor and measure my instructional impact on student learning along with a more formal opportunity for them to demonstrate their learning. On the assessment, I included a question where I asked students to identify and explain 1 thing that they had learned about sentence forms, sentence types, or conjunctions since we began studying them. When reading student responses, I noticed that a significant number of students commented that they learned how conjunctions worked to connect ideas within sentences.

The insight I gained from the experience and believe to be worth sharing with other educators is I/we should avoid assuming that students in intermediate grades arrive to our classrooms with a clear knowledge and understanding of how to connect ideas within a sentence using conjunctions or that they even understand the difference between coordinating and subordinating conjunctions. I think that at times reviewing and at other times explicitly teaching students how conjunctions function within a sentence serves to positively impact all students learning.

Structured Literacy Shift #3: Progress Monitoring

As I continue my learning journey with Structured Literacy, I’ve been reflecting on the shifts that have had the biggest impact on my teaching.

Read about Shift # 1:Structured Literacy Shift here.

Read about Shift # 2: Morphology Instruction here.

As I continue documenting the shifts I’ve made , today’s post focuses on a practice that has transformed the way I understand my learners: Progress Monitoring.

Progress monitoring is an assessment method that refers to quick, ongoing checks that help teachers see how students are responding to instruction and meeting learning goals. It is not something students prepare for, and it does not function like a traditional test. Instead, it is a form of assessment for teachers—a tool that guides planning, grouping, and next steps. Progress monitoring offers an authentic look at what they can currently do.

In a Structured Literacy, progress monitoring helps us:

- Identify which skills students have mastered

- Pinpoint where skills are emerging

- Adjust instruction to close gaps quickly

- It gives teachers data to ensure small groups are based on current needs, not assumptions

Essentially I have found these small, frequent checks make learning needs visible much sooner. Progress monitoring is also an equity practice as it ensures instructional decisions are based on data, not personal biases.

Some ways progress monitoring fits naturally into my literacy block:

- Quick phonics or morphology checks based on a scope and sequence

- Using technology to get reading fluency snapshots

- Writing dictation samples

- Reviewing writing samples for transfer of skills

My reflections

Since making progress monitoring a regular part of my routine, I’ve noticed:

- More targeted instruction—I know exactly which skills need to be retaught or extended

- Flexible, responsive groups that actually match current student needs

- Earlier identification of students requiring support

- Improved student confidence because I can give timely meaningful feedback with actionable steps

- Clear, concrete evidence of growth to share with families and support teams

You can also review the ETFO assessment website for more information about ongoing assessment.

What did you see today?

Hello Fellow Travellers,

Progress reports have gone home and we are moving through the school year. I hope you are well and are taking care of yourselves.

I’m Here Now

I used to do other jobs before, as a Grade 7-8 science teacher, then SERT in the Grade 6 to 8 years, then K-3 teacher etc. But I am here now. I do not have a classroom of my own is one way of looking at it. Another way, is to think that all classrooms into which I am invited are my teaching-learning spaces too.

I am here now. This is one such recent memory of being in the moment, teaching and learning.

One Monday Morning Recently

As with every stage of life when things change I remind myself that I’m here now so there’s more looking ahead with hope and anticipation than looking back with nostalgia. It was Monday morning and I was in a Grade 2 classroom at the farthest school on my list. I’d not been in this classroom before though I’ve met the students in Grade 1.

What Did You See Today?

On my drive, as I travel up from the southern end of the region, I see the land change and I see horses.

When I’d worked with them then, they’d asked me “where do you live?” And when I’d shown them the general area, some of them had asked, I remember “What did you see on your way up?”

Something Lost, Something Gained

I remember when my younger child learned to read I had felt as if a part of my life changed forever. So also, as I’ve missed this part of a classroom teacher’s job since 2020. In the early days I remember I used to look through picture books and think “oh that’ll be great to read aloud” and then I’d remember that I didn’t have my own classroom anymore. It took time to get used to the idea that it’s possible to belong nowhere yet be a part of everywhere.

The Book

The book I’d chosen was one I have liked as a reader as well as an educator. Friends and colleagues had read and recommended it to one another over the years. That said, I encourage all readers to consult your school board’s Text Selection and Guidelines.

We’ve Read This Book Before

The colleague who’d invited me and I had decided I’d bring a book to read, I’d introduce myself and I’d review her expectations chart… you know how the routine goes.

I did the first few things and as I took out the book the students said, “We’ve read this book before.”

So Let’s Think Differently ( I thought)

I always carry a few copies of copies of picture based prompts for exactly such a moment . I handed out the cards and began to read. I asked the students what they could see in the pictures as I read and what they could tell from their previous reading. They were eager and listened, then responded.

We read together, we noticed some things, we commented on some things, we made connections.

Then a student asked “do you have these cards for our class?” “Yes, I do”, I said and I left a spiral bound mini version with him.

Previous Connections

Although I recognize students from previous years I don’t crowd their space and place when I meet them again. But after giving the student these cards, as I was moving away, I was stopped with a soft tap on my wrist.

“I remember you”, the student said softly. You come from far away and you see horses on your way to our school ”

“Yes, I do”, I replied.

It appears that “All Are Welcome” wasn’t just the title of the book I’d chosen.

It was also my experience in this classroom. For such moments, I am deeply grateful.

I want to invite you to write back directly (if you know me outside this space) or through this space to share what you see that welcomes you into your teaching and learning spaces.

With You, In Solidarity

Rashmee Karnad-Jani

Teaching Ideas for Award Winning Picture Books Part 2: Imagination and Humour

The children of Ontario get a chance every year to vote for their favourite Canadian picture book from the Ontario Library Association’s list of nominees. Some of my most beloved books are from this category and as a teacher I’ve used them countless times. The two books featured in this blog both demonstrate the fantastic imaginations of writers and illustrators. Plus, these books both feature humour as a literary device to make these stories unforgettable.

The Boy Who Loved Bananas by George Elliott; illustrated by Andrej Krystoforski

2006 Winner of the Blue Spruce Award

Matthew loves the monkeys at the Metro Zoo so he decides to be like them and only eat bananas. Suddenly he feels an itchy sensation and he turns into a monkey. His parents try all kinds of interventions but everyone says Matthew will stop being a monkey when he wants to stop. He gets up to many types of mischief while he is a monkey, including influencing all the kids at school to eat bananas. The principal joins the trend too! The story ends with Matthew switching to peanuts and he is pictured sitting at his desk in his classroom as an elephant!

This book is a terrific story starter for shared, partner or independent writing. To analyse the writing style we realize that the story can be broken down into parts:

*The main character is introduced and is shown to love the animal he is going to turn into;

*The reader must suspend their disbelief and accept that the main character “transmogrifies” into an animal;

*The main character visits many practitioners but cannot be cured;

*The parents learn to accept their child the way he is;

*Just when we think he will become human again, the main character changes into something else that he likes.

Using The Boy Who Loved Bananas as an example we can emphasize that there is no harmful violence in the story. The type of humour is quite silly and uses exaggeration such as Matthew climbing the flag pole or the principal eating bananas under his desk. When students are creating their own story, they can also use exaggeration to add humour to their ideas.

It is possible to go a step further and have students add detailed illustrations to their work. Look carefully through the original book and notice how the other characters’ facial expressions show their reaction to what is happening.

Having students create books with illustrations is a terrific project. It helps them understand the publishing process and they end up with a wonderful creation. The stories could be put on display in the class library so that they can read each other’s work. I have found that when we send these books home, many families treasure a book created by their child.

If Kids Ruled the World by Linda Bailey; illustrated by David Huyck

2016 Winner of the Blue Spruce Award

Similarly, If Kids Ruled the World asks us to suspend our disbelief and imagine the world with children in charge. The story stresses the fun and silly antics that would occur in this situation and as you can imagine, kids absolutely love it. The illustrations add a tremendous amount of humour to the story as we see multiple characters on each page acting out everything from unusual pets like giraffes and ostriches to bubble fun in a swimming pool to a trampoline sidewalk.

This story would make a wonderful lead up to an art lesson where each student illustrates their answer to the question: What funny things could happen if kids ruled the world? Assembling all their work into one class book makes a very popular item in the class library.

Both of these books can be adapted easily for K-3. Depending on your students, you could use these stories with older students too. I have had success partnering with older students to create picture books as an assignment. These books are perfect examples to demonstrate how to use your imagination and humour to create a hilarious and unforgettable story.

Happy Reading, Writing and Drawing!

Brenda

Celebrating to Learning Holidays

As we move towards the winter holiday season, it is natural to discuss the different holidays we all celebrate. As an educator who works in culturally and linguistically diverse communities, I often question myself: how do I honor students’ identities and be inclusive during this season?

I feel that the distrinction between learning and celebrating holidays is key.

Learning about holidays positions it as a place of inquiry. Students explore traditions, stories, and histories without being asked to participate in practices unauthentically. This shift supports equity and belonging.

What it can look like? Here are some suggestions I have personally used:

- Reading diverse texts: Allow students to form connections to their own experiences (encourage critical thinking)

- Centering Student Voices: Students may want to share how they recognize a holiday. This optionality keeps students from feeling put on the spot or singled out as cultural representatives.

- Curriculum Connections: It aligns wells with Social Studies (identity, community, traditions, citizenship), Literacy (informational texts, narratives, speaking and listening) and The Arts (appreciating—not performing—cultural practices)

- Ask “What have you learned about this tradition?” instead of “How do you celebrate?

- Collaborate with Families: Share your approach with families understand that the classroom is learning-focused and give them the chance to share if they feel comfortable

- Reflect Regularly: Ask yourself, “Whose traditions are being centred? Whose are missing? Are all students able to engage comfortably?”

Moving from celebration to learning isn’t about removing joy; it’s about widening the circle of belonging. When students see that their teacher approaches holidays with curiosity, care, and humility, they feel safe, respected, and represented.

Measure With Your Heart

At the beginning of the school year, I ease my working mom anxiety by watching a lot of videos about quick after school dinner recipes. While there are hundreds of things to worry about related to teaching every day, somehow this makes me feel better and more prepared to tackle these sometimes exhausting fall beginnings every year.

I start out looking at the main ingredients required, the measurements so I will know how much to purchase and whether it’s simple enough for me to figure out on my own. As I watch the video and see the cooking techniques and instructions, it starts to make sense to me. I can imagine the textures, the tastes – even see how many pots and pans I’ll have to clean after dinner. These videos are entertaining and also help me to gain confidence in trying new flavours or learn how to tweak my tried and true recipes.

My favourite phrase is when the creator gives permission to “measure with your heart”. This small four word sentence honours that everyone’s tastes may differ; your family may like a little less salt and a little more garlic, or might prefer maple syrup over honey for a sweetener. The small tweaks personalize that recipe and help me to make it my own. When I measure with my heart, I think about who I am cooking for; family, friends, or even just myself and that recipe becomes customized with them in mind.

When I get the opportunity to meet students in these early fall days, I’m still following some of those tried and true ‘recipes’ at the beginning of the school year – lots of smiles, spending time getting to know each other, building a community together. I work my way through the measurements – assessments that help me to learn more about their academic experiences and how I can best meet their needs as their teacher.

But somehow, without my noticing, I start to measure with my heart. I see all the unique qualities and personality traits of the students and they start to learn a little more about me, too. Some may need a little more gentle encouragement and others like to laugh and joke around with me. I learn who has siblings and who has a hamster and who takes swimming lessons on the weekend. I ask about these experiences that are important to them – personalizing the way that we show care for one another. Maybe it’s suggesting books that centre their identities in language class; maybe it’s using real life examples that help them feel seen in math class. Just like cooking, when I measure with my heart I think about who I am teaching – not just as students, but as children who are brilliantly unique and gently adjust the flavour of our classroom with them in mind.

As we move into the unending deadlines that always seem to be present in education, I’m going to remind myself to measure from the heart every day. To think not just about what students need to learn, but the ways our classroom can best reflect how they need to learn. Perhaps it’s a little more scaffolding at times or a more hands-on experience in other subjects. Maybe Monday needs to be a little sweeter than the other days while Friday needs to be more spicy and bolder. There’s no recipe that can guarantee what we will need most each week; I’m just going to measure with my heart.

Here, now

Those of you who have had the privilege of being ESL teachers will know the look I am about to describe. It’s the expression on students’ faces when you arrive at the classroom door to collect them for tutorial support, their smiles lighting up the room as they realize it’s their turn to go with you. Other times you might notice a jump in energy when you walk in, as students suddenly rush to grab their pencils and head over in enthusiastic anticipation. Yes, ESL support classes can create an incomparably safe, fun, and dynamic environment full of rich learning. It’s a smaller space, quieter … where a few familiar students and a dedicated, specialized teacher provide the extra scaffolding, time, and support new students may need to find their footing and continue to learn.

It goes without saying that many multilingual language learners appreciate and look forward to these welcoming and affirming tutorial programs.

But …

But.

Not all students do.

Those of you who have been ESL teachers will also be familiar with a different look, I think. Sometimes, it is an older student who looks a bit embarrassed, not wanting to be singled out in front of peers as needing “help”; sometimes it is a student who is passionate about the next lesson topic, and looks frustrated and disappointed they will miss it; other times the student is unmistakably crestfallen, having worked tirelessly on their art project or science demonstration, only to find they will not be present for the first part of the class presentations on it; one of the worst is a quiet look of sadness, the student’s desire to stay with their friends seeming to hang in the air in front of you, everything about their expression telling you they just want to stay and participate in everything their peers are doing.

Make no mistake, these looks are not the result of subpar teaching or lackluster ESL learning programs; on the contrary, ESL teachers are some of the most talented and knowledgeable educators among our ranks. It is simply a part of that undeniable truth, that students have unique and varying learning needs, and that while some may appreciate and benefit from tutorial instruction in the traditional sense, others need something else. They want to stay and be included in their learning community in the classroom, be the same as their friends, and learn English and curriculum in the process.

In my last blog entry First, then, I described some of the potential academic pitfalls of isolated ESL tutorial instruction, where educators teach separate programs with little to no communication and collaboration. In such isolated models, students may not have as many opportunities for scaffolded support and recycling of key language structures needed in the mainstream classroom, potentially resulting in reduced linguistic development and curriculum access. However, academics are not the only consideration in this scenario. The innate desire we all have as humans to contribute and be included is equally important. And in decades’ past, when ESL support models overwhelming defaulted to isolated tutorial support, we may have met the needs of some students … but not all.

Implicit in a model that requires students to learn English as a separate subject before they are able to participate in classroom lessons is the assumption that students do not have the ability to participate as they are, here and now. That their current linguistic repertories are irrelevant to learning. That their rich experiences and skills do not count in school. That they are not enough.

Fortunately, today’s ESL teachers are no longer relegated to isolated islands of instruction; classroom teachers and ESL teachers can now actively collaborate with one another to ensure MLLs are included in daily instruction, and have access to a full and robust curriculum, with the language supports they need to do so. To accomplish this, some educators co-teach in the same classroom, ensuring MLLs can stay with their peers and continue learning English; some teach separately but communicate with one another, so that their language programs are aligned and mutually-reinforcing.

All of this is well and good if – if – proper supports for educators are in place, with students’ needs centred. And regardless of support model used – tutorial, or integrated, or some wonderful combination of the two – the professional judgement of teachers, coupled with adequate funding and teaching staff, are critical to choosing, creating, and sustaining responsive learning programs for students.

I will not repeat the myriad of ways collaborative, inclusive teaching models can be accomplished. I will however offer the link again, to ETFO’s infographic quick guide “Collaboration and Co-teaching for MLLs” as well as additional infographics in the same series, “Translanguaging” and “Program Adaptations”, which detail how students’ first languages and background knowledge can be included and affirmed in the classroom, and used for rich curriculum learning. ETFO Secure – Supporting English Language Learners Resources

Wishing you the best of luck in re-imagining your classroom environments, in which all students’ identities, knowledge, and languages provide bright paths to learning. Where they are more than enough … right here, right now.