How do you support and program for newcomer students in acquiring English in the mainstream classroom?

This is a question many educators have when they receive newcomer English language learners (ELLs) in the classroom. In my last blog post, I wrote about why questions like these are so common. Elementary ESL programming documents detail the important role of accommodations and modifications to curriculum when planning for ELLs, but do not outline a scope and sequence of English language acquisition. Classroom teachers – particularly when they are teaching the older elementary grades – often wonder how they will teaching foundational English to the ELLs at the same time they teach non-English learners. While many younger elementary ELLs in the primary years thrive alongside their peers who are also learning letter sounds and vocabulary, older students sometimes struggle without opportunities to build their English oral foundations, as well as the right adjustments to make learning accessible.

Here are some strategies for teaching English to ELLs in the junior and intermediate classroom.

Start With STEP

The Steps to English Language Proficiency (STEP) continua/framework often gets overlooked as a tool for planning instruction and creating appropriate learning expectations for English language learners. Make sure you have regular access to the STEP placement of the ELLs in your classroom, so you can adapt instruction and modify learning expectations accordingly. For example, if a student is approaching STEP 1 or is at STEP 1, you will know that they are in the emergent phases of acquiring English. When you plan a lesson in Social Studies, for example, you will want to use that knowledge to develop learning activities that enable that student to engage in the learning: introducing vocabulary at the start of a lesson, or using visuals to illustrate content (we will talk more about creating entry points into curriculum next).

Most importantly, you can use STEP to modify learning expectations that you can use for assessment and reporting purposes. Record the specific learning expectations you establish for English language learners in a doc or a template so you are ready when assessment time comes. An example of an ESL modified learning expectation might be:

Grade 7 History Expectation:

(Student will) “analyse some of the main challenges facing various individuals, groups, and/or communities, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit individuals and/or communities, in Canada between 1713 and 1800 and ways in which people responded to those challenges.”

Modified for a student in STEP 1:

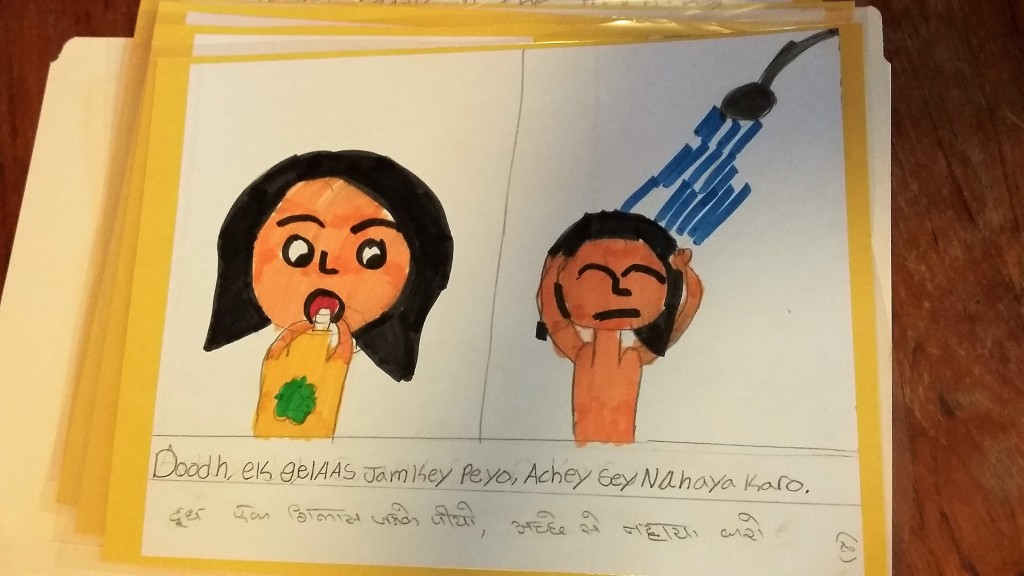

Student will describe a series of images, using picture word induction model and translanguaging, to describe some of the main challenges facing different communities, including First Nations, Métis, and Inuit, in Canada between 1713 and 1800.

Create Entry Points for ELLs into Curriculum Content

Teaching content based subjects, especially to older ELLs can be a challenge when much of the content the class is developed for students with higher levels of language proficiency. This is particularly true in subject areas like science, history or geography. Provide your ELLs an access point into whole class instruction by offering text sets, or sets of texts that offer the same information through a variety of formats (articles, leveled texts, charts, visuals, or media). Students can explore text sets and gather information from them for research or to complete learning tasks. Multimodal content offerings are also effective: “something to read, something to watch, and something to listen to” is a good mantra to keep in mind. Finally, encouraging students to translanguage or access multilingual texts is an excellent way to support them in using their primary language while also meeting the content goals of a subject.

Set Social Learning Goals for Your Class

I have many opportunities to collaborate with experienced ESL teachers, and one fantastic tip one teacher told me was to introduce social learning goals with the entire class. Setting social goals for the entire class not only gives English learners an opportunity to use essential questions like “how are you?” or “how was your day?” regularly, but creates an opportunity for them to engage in basic conversation with their peers on a regular basis. Social goals may also include making a point of helping others, including a student who may feel left out, practicing cooperation skills, or using positive body language. Social goals also help students to build healthy relationships with one another, while learning important social skills as well.

Incorporate Language Scaffolds into the Learning Environment

All students, especially ELLs, benefit from language scaffolds and reference charts. Hang charts and posters of sentence starters/models, transition words, vocabulary lists, verb charts, pronouns, and labels on classroom items wherever possible for easy, at a glance support for students. Change your word walls or charts to reflect content learning, and make a point of frequently using the words and phrases you want to emphasize. Having opportunities to hear and apply new words and phrases are essential for language learning, so make a point of using words and phrases you have featured on a regular basis.

Use English Learning Apps and Games (With Caution!)

English apps and games are a tricky topic. On one hand, we want to focus on building English communication skills through live conversation, listening activities, and social interactions; on the other hand, apps can do the powerful job of introducing key vocabulary and phrases in a fun and engaging way.

If you do use language learning apps like Duolingo or Mondly in the classroom, make sure that the time students spend on them is limited (ex. 15 minutes a day). School can be a critical time for interacting and practicing spontaneous communication skills, so apps are usually best used in limited timeframes or at home.

Understand how to Use English Learning Resources Effectively

There is no shortage of ESL resources out there, as millions of people around the world are learning English all the time. However, you will find that many of these resources are not designed for a single student in a mainstream English medium classroom, but for classes entirely composed of English language learners. If you do use an ESL focused workbook or resource, use it flexibly and in the context of the broader programming all students are learning. Such resources may be used if the ELL has the opportunity to receive higher tier instruction and support in an alternative space, or at home with their families.

Keep the Big Picture in Mind

Finally, it is important to practice big picture thinking and remember that the learning and instruction newcomer ELLs experience in your class is just the start of a much bigger journey for them in Ontario schools. Furthermore, the journey of every language learner will be different. Acquiring proficiency and fluency in any language takes years of learning, immersion and practice. Set high but realistic learning expectations for English learners, keeping in mind that the time they spend in your classroom is a critical step in a much longer pathway toward mastering the language.

Read Part 1: Supporting English Language Learners in the Mainstream Classroom