Music Class can be tricky to navigate for our ELLs (English Language Learners). Although music is really fun and engaging, learning lyrics to songs and terms for describing music can be challenging to remember.

Lyrics to songs can be difficult for ELLs as there are often slang words, incomplete sentences or words that are used in unusual ways. Lyrics manipulate grammar rules and each genre can have its own style of communication, depending on its origin. In addition to lyrics, vocabulary for music has the same challenges as many content subjects, which is that the vocabulary is often not used in daily life. You don’t hear people talking about how forte, vivace or legato a song was. As the vocabulary is only used for such a small portion of their school week, it is very hard to internalize.

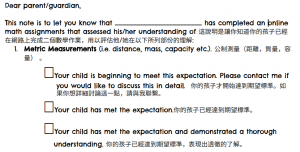

My student population has around 70-80 percent of students on the STEPS of Language Acquisition. In trying to help my ELLs be successful in music class, I have used the following:

1) Song selection: My team is very selective when choosing songs to sing in class, and we are always looking to make sure songs are not too long, often repetitive and that new vocabulary is not too overwhelming for students to learn.

2) Patience: We take time to let students internalize one section of the song before we move onto the next. If we are learning a song that is a little longer, we only focus on one verse for part of a class and visit the next verse in subsequent classes.

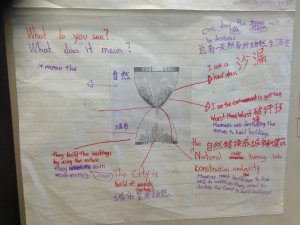

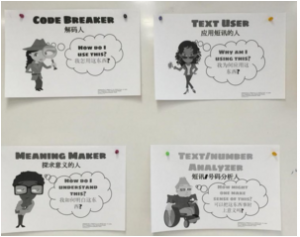

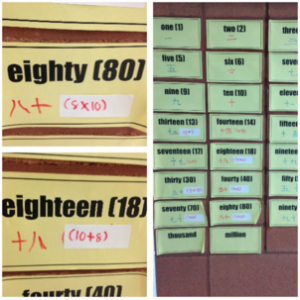

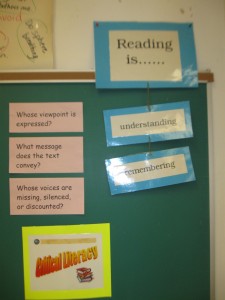

3) Visuals: There are diagrams and visuals to support students in discussing music. (You can find mini posters about the elements of music on the website Teachers Pay Teachers). Also, illustrating a song can help solidify meaning.

4) Actions: We often add actions to many songs to help us understand the meaning of what we are singing.

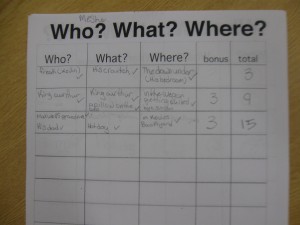

5) Cooperative Learning: We do some whole group and teacher led instruction to learn some new vocabulary and lyrics. However, more often, students work together as pairs or groups towards internalizing the lyrics and their responses to music.

6) Use music that represents the culture and language of your students: Using songs from a student’s culture allows them to feel valued and they become the expert in the room. Finding authentic arrangements and scores can be difficult. Making a connection to a member of the community that can help you is a very important asset.

7) Make it fun: Ultimately, music should be a fun way to engage with language. So encourage the students to enjoy themselves!

Even though music can be challenging, it can also be very supportive when learning a new language. About 15 years ago, I decided to move to Japan to be a teacher. I ended up loving it so much that I stayed there for three years. In my own personal journey of learning a new language and writing system, music played an important role. I listened to a lot of Japanese music and bopped and bounced along to the music in my home, car and at school. New vocabulary stuck in my brain from the songs that I heard, and I enjoyed learning how new vocabulary was written in Kanji (the Japanese writing system) from the inside of CD covers. Listening to music was great as it was the one Japanese activity in my day that didn’t require a response from me. Music can play a very important role in the acquisition of language.

The final stage of this unit is to transfer the learning that has occurred to an independent reading task they complete. This is called their Book Project. They are able to select a book that meets the following two criteria:

The final stage of this unit is to transfer the learning that has occurred to an independent reading task they complete. This is called their Book Project. They are able to select a book that meets the following two criteria: