One thing I have always loved about being an educator is that we have two “new year’s”: one in September when the year starts, and one in January when the year changes. Travel is a luxury that I feel so fortunate to enjoy during those moments: it is the perfect time to reset my thinking and refocus on the time ahead.

In the last year, the desert has been a special place for me to reconnect with nature and think critically about how we learn about the world. Learning about the environment from two very different cultural approaches has helped me to build a greater appreciation for different ways of knowing and seeing the world.

Learning the Sonoran Desert

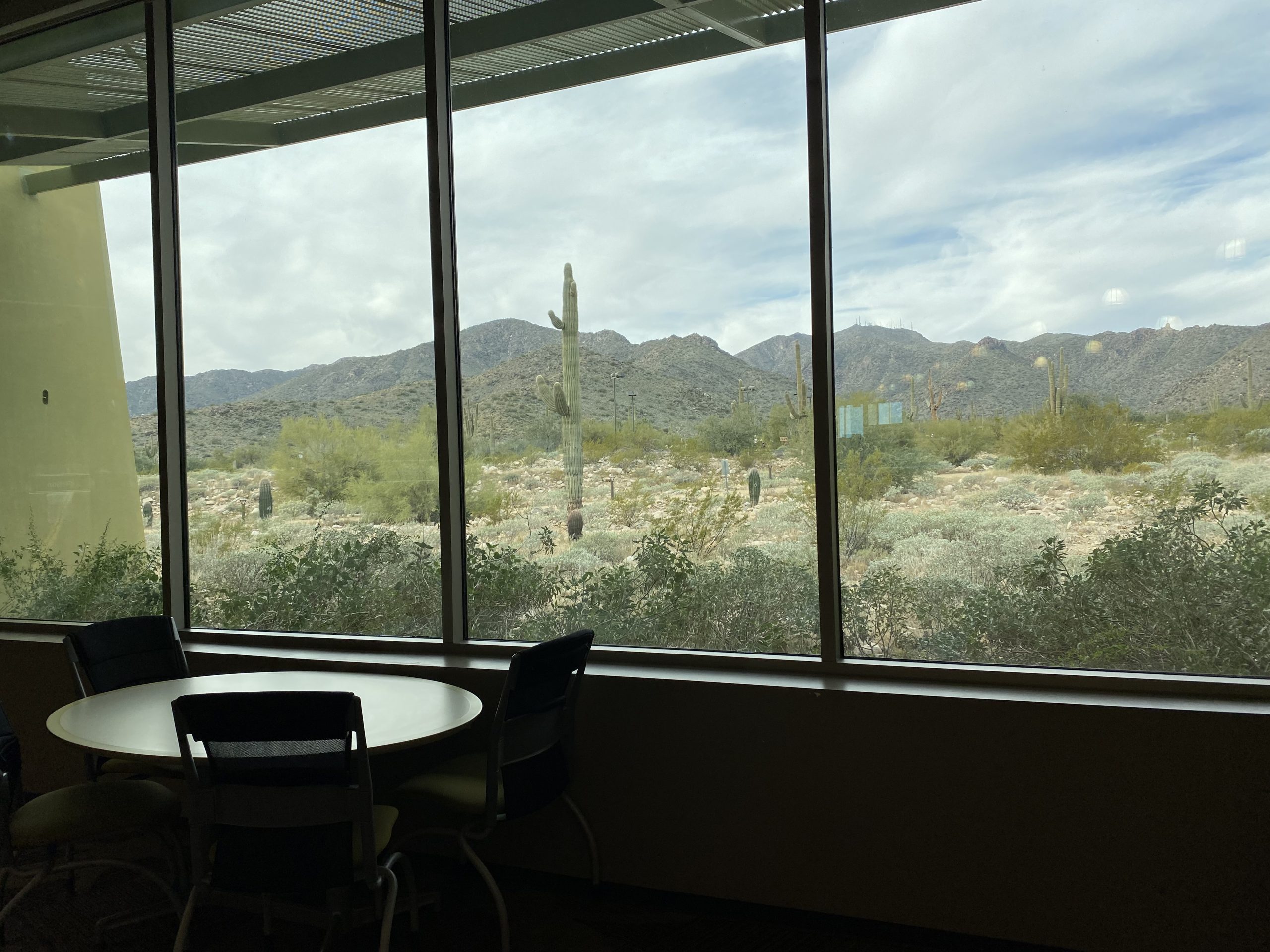

I had the privilege of spending time in Arizona last January, and came a cross a place called the White Tank library. This place had an entire wall of back windows that faced a sprawling nature reserve. In the same building beside the library was a nature centre and bookstore. The bookstore had dozens of books for kids and adults themed on desert flora and fauna, particularly the notorious javelina (totally worth Googling if you have never heard of this animal!). There were desert spiders, snakes, and other creatures on display for people to look at, and guides on site to give information about them.

The trails at the back of the building were well manicured, with information signs throughout the walk explaining the different variety of cacti. Even if you didn’t feel like reading, the site was absolutely spectacular to look at. The trails looked well cared for, and loved by the locals we saw in technical fitness gear running and hiking through the grounds.

The library and all of its resources resonated with me because it aligned with my personal experience of learning – books, guides, and clearly defined trails that I could navigate easily. Immediately I imagined how great it would be to take students here, and how easy it was to connect science and literacy learning.

A Jaunt in the Sahara

On another desert trip last summer, I went on a short tour of a small section of the Sahara in Egypt. Desolate, mountainous, and nearly unbearably hot, this desert contrasted starkly with Arizona’s Sonoran landscape. A wild and bumpy jeep ride took us about 30 minutes into the desert.

The excursion took us to a desert village largely set up for tourists. According to the guide, the locals quite understandably did not like tourists peering into their homes, so they separated their homes from the area that foreigners could explore. Constructed of simple, open air buildings and a space where tourists could ride camels led by local residents, the whole experience of the place beautifully showcased the arid, mountainous landscape.

We looked into a small mosque, watched a young girl demonstrate bread making, and drank hot tea. A small hut featured local animals such as lizards and bugs. A rocky climb up a hill gave a view of the actual village homes in the distance. Completely unmarked, it was a struggle to climb until we became accustomed to climbing the steep and rather unstable ground.

And while the rustic tourist site bore zero resemblance to the modern, well-funded Arizona library and trails, it struck me how two completely different cultures had created similar experiences for people to learn about the desert environment.

The Takeaway

There are so many ways to experience and learn from the outdoors. Why should we limit ourselves, and the students we teach, to a single perspective?

It is wonderful and enriching to have books, exhibits, panoramic windows, and guides to help us navigate nature. It is also equally great without all of these things, and learn from observing the way that people sustainably maximize the resources they have access to.

Outdoor education has come a long way in Canada. More and more, schools are embracing Indigenous ways of knowing, particularly when it comes to stewardship and wildlife protection. Books like Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass have offered powerful, Indigenous perspectives on the natural world and scientific learning.

It is an exciting time to embrace the different ways we can understand nature. In a time when stories of forest fires and climate change have become part of the daily news cycle, alternative ways of learning are more critical than ever.