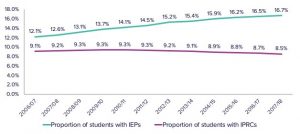

The Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) (October 2019). Recent Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO) test scores show over 25% of Grade 3 students and 53% of Grade 3 students with special education needs did not meet provincial standards.

The OHRC cites that students who cannot read struggle with many aspects of school and are more vulnerable to psychosocial stress, behavioural issues, bullying and much lower levels of educational achievement (Schumacher, 2007). The result of these challenges means that these students face life-long consequences including , homelessness, and involvement with the criminal justice system (Bruck, 1998; Macdonald, 2012); Maughan, 1995; Rice, 2001).

All students with reading disabilities, such as dyslexia, have a right to learn how to read. The OHRC is concerned that these students are not getting the supports they need to become literate. This is particularly challenging when students are not receiving early intervention and supports that are known to be effective in increasing reading ability.

The OHRC inquiry wants to hear from parents, student, and educators from across Ontario to determine if school boards are using evidence-based approaches to meet students’ right to read. The OHRC will be assessing five benchmarks as part of an effective systematic approach to teach all students to read which includes:

All about Reading Disabilities

- Dyslexia is a learning difficulty which presents as difficulties in spelling, phonological awareness (i.e. sounds of letters and words), verbal memory and verbal processing speed

- reading disabilities are not related to a person’s intelligence

- dyslexia and other reading disabilities are a result of difference in brain structure

- dyslexia tends to run in families and has an inherited rate of up to 80% (found in the chromosome regions 1p34–p36, 6p21–p22, 15q21 and 18q11)

- dyslexia is more common in boys than girls with a (two fold increase in the risk for boys compared with that in girls)

- 20% of children with dyslexia also have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- reading disabilities do not go away as people get older and cannot be cured

- reading disabilities can also be caused by brain injuries and/or dementia

- people with reading disabilities can also have challenges with language, motor co-ordination, mental calculations, concentration, and personal organization

- people with learning disabilities often lose their sense of ability, dignity and self-worth, and may develop depression and anxiety

- due to less access to publicly available psychological assessment funding students with lower socioeconomic status may never get the testing they need to evaluate their reading disability

How can teachers support students with suspected reading disabilities?

- promote early identification through tracking reading levels and psychoeducational assessments

- develop effective interventions and accommodations support through an Individual Education Plan (IEP)

- instruct through scientific evidence-based and systematic instruction in reading

- advocate for more support via funding of psychoeducational assessments as parents may struggle financially to get assessments, interventions and accommodations for their children, and in many cases have no options, if able, to pay for services privately

Empowering Readers

As a contained Communication Classroom teacher, I am trained to use the Empower™ Reading Program provided by The Hospital for Sick Children (Sickkids). This program, developed by Maureen W. Lovett and her team, is based on a series of evidence-based reading interventions that reinforce skills in reading, comprehension, and writing. As the SickKids’ website states “ The Empower™ Reading Program includes decoding, spelling, comprehension and vocabulary programs that transform children and adolescents with significant reading and spelling difficulties into strategic, independent, and flexible learners. The success of the program is proven through the extensive rigorously designed research conducted by the research team.”

There are four distinct literacy intervention programs that comprise the Empower™ Reading Program:

In my classroom of Grade 4/5 students who cannot read at grade level, I’ve seen dramatic results in students increasing their reading ability several grade levels in a 2 year period. One of my students, this year, went from a Kindergarten to mid-grade 2 level in 4 months. Students usually stay in the Contained Communications class for about two years and return to a mainstream classroom.

In the 3 years I’ve used the Empower™ Reading Program Grades 2-5 Decoding and Spelling program, I typically have students entering the program reading at two or three grades below level and leaving at a grade 5 reading level. The program is well laid out for teachers and students. I appreciate that it’s a hour of my day that has already been planned. Teachers receive 3 to 5 days of training and are provided with face to face Empower support check-ins. Teachers are also required to provide assessment tracking via PM Benchmark assessment, Empower Sound and Word Assessments, and the Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement (KTEA-III) testing.

As a teacher, I strongly advocate for boards of education to take on the Empower™ Reading Program, not only because of its effectiveness, but because it changes students’ lives by boosting their overall self concept and their ability to thrive as learners.

Finally, I know what it is like to not read and write well as I struggled for years in all levels of my academic studies. I failed grade 1 as I was very uncoordinated and a slow learner. In my time as a elementary, secondary, and university student, I was told that I made careless mistakes and that I needed to work harder. I had grades taken off my essays and exams due to poor spelling and grammar. I did not come out to colleagues and professors as being learning disabled until I was accepted into my PhD program as often people would not believe me.

The biggest challenge with being learning disabled was my lack of confidence in myself as a person and in my ability to read and write. I am still a poor speller. My self-worth remained low for a significant part of my life and I lived with depression and anxiety. I posit that my drive to overachieve in education is a compensary response to my life as a learning disabled person. Even though I present as being highly self confident, I still struggle with my confidence today.

I ask you as an parent, educator, and/or student to push for more support and intervention for Ontario students who deserve the Right to Read as the right to education is a Human right.

Collaboratively Yours,

Dr. Deborah Weston – B.Sc., B.Com., B.Ed., M.Ed., PhD OCT# 433144

PS: It took me 4+ hours to research and write this blog using a talking word processor.

Media contact:

Yves Massicotte

Communications & Issues Management

Ontario Human Rights Commission/Commission ontarienne des droits de la personne

416-314-4491 Yves.massicotte@ohrc.on.ca

The Right to Read public hearings will run from 6 to 9 p.m., with registration beginning at 5:30 p.m. at all locations.

January 14, 2020: Brampton – Chris Gibson Recreation Centre 125 McLaughlin Rd N, Brampton, ON, L6X 1Y7

January 29, 2020: London – Amethyst Demonstration School Auditorium, 1515 Cheapside Street, London, ON, N5V 3N9

February 25, 2020: Thunder Bay – Public Library – Waverley Community Hub Auditorium, 285 Red River Road, Thunder Bay, ON, P7B 1A9

March 10, 2020: Ottawa – Nepean Sportsplex, 1701 Woodroffe Avenue, Nepean, ON, K2G 1W2

- Filling out a survey at least two weeks before the hearing they want to participate in and being selected to make a presentation up to seven minutes long

- Attending a public hearing and registering to speak for three minutes during the “open mic” session

- Attending a public hearing to observe.

References

Bruck, M. (1998). Outcomes of adults with childhood histories of dyslexia. Reading and spelling: Development and disorders, 179, 200.

Macdonald, S. J. (2012). Biographical pathways into criminality: understanding the relationship between dyslexia and educational disengagement. Disability & Society, 27(3), 427-440.

Maughan, B. (1995). Annotation: Long‐term outcomes of developmental reading problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 36(3), 357-371.

Rice, M. (2001). Dyslexia and crime, or an elephant in the moon. In 5th BDA International Conference: At the dawn of the new century, York.

Schumacher, J., Hoffmann, P., Schmäl, C., Schulte-Körne, G., & Nöthen, M. M. (2007). Genetics of dyslexia: the evolving landscape. Journal of medical genetics, 44(5), 289–297. doi:10.1136/jmg.2006.046516