Are mindfulness activities a part of your program?

Each day more than the last, it feels like mindfulness activities are being promoted for classroom use as part of a solution to what we are currently experiencing as humans on planet earth.

I am not a mindfulness or meditation expert, nor am I trained in yoga instruction.

I am however, a curious participant and reflective user of daily mindfulness opportunities in the classroom.

In a blog post for The MEHRIT Centre titled ‘The Self-Reg View of Mindfulness (Part 1)’, Dr. Stuart Shanker, an expert and leader in the field of self-regulation discusses mindfulness through the lens of self-regulation. He states the goal of mindfulness activities is not “developing techniques to suppress or flee from unpleasant thoughts and emotions” but rather to “pay close attention to them with the hope that, over time, you’ll be able to tolerate things that you have hitherto tried to repress or avoid”.

Shanker highlights that one’s ability to engage in mindfulness and meditation experiences are not instinctive, for neither adults nor children. He acknowledges that for some people, the “act of concentrating on their breath or their emotions” while attempting to sit still or quietly can bring great amounts of stress or anxiety.

Shanker cites the work of Dr. Ellen Langer and emphasizes the importance she places on understanding “mindlessness” in order to create an understanding of the term mindfulness.

This resonated with me.

If I am not achieving mindfulness am I engaging in “mindlessness”?

It had never crossed my mind how dangerous this dichotomization could be.

Mindfulness or mindlessness?

Thinking about those who do not find success or find stress in widely used mindfulness activities… are they still being viewed through a positive lens? How can I expose my students to meaningful mindfulness activities that are positive while maintaining a sensitive and trauma informed approach?

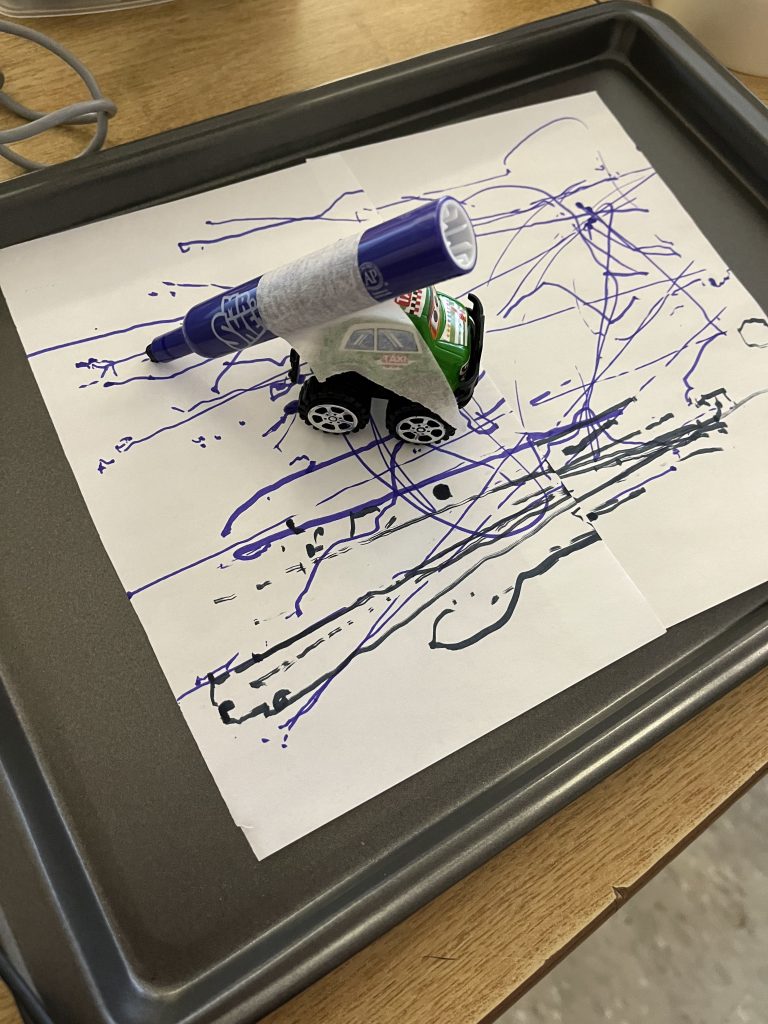

As Shanker points out, a state of mindfulness is unique to every individual person and should be achieved as such. Additionally, what calms you “may change from day to day, even moment-to-moment”. Mindfulness must be differentiated and unique: Like any new concept introduced, students need time, patience, space and practice in order to discover what helps them feel calm and under what circumstances. Contrary to this statement, students also need time, patience, space and practice while they discover what does not work for them in order to feel calm.

Accordingly, the act of differentiating these completely personal moments of mindfulness feels to me like in order to be genuine, they need to be voluntary. To allow for students to discover their own state of calm: Mindfulness opportunities must be optional. Although necessary, offering students a choice of participation in mindfulness activities feels confusing or worrisome. What if they choose not to participate? Can they match the calm state of their classmates in different ways to avoid disrupting the calm state of others? Should mindfulness be practiced as a whole group? What are the benefits to whole group mindfulness instruction? What are the disadvantages to a ‘one size fits all’ approach to mindfulness?

Have I perfected the use of mindfulness in my classroom? No.

Does this exist? Likely not.

Nevertheless, I continue to reflect on the polarization of mindfulness and “mindlessness” and what this means to me.

What does mindfulness mean to you? How does this influence your teaching practice?