What’s the difference between thinking and understanding? More specifically, how might one distinguish between the activity of thinking and having understanding. Is there even a difference? This got me thinking… How I might invite educators to a conversation about assessment practices using a common understanding of assessment through the lens of Ontario’s standardized assessment rubric, The Achievement Chart. Most of the assessment resources that I usually refer to spoke more about the assessment process and the importance of assessment as, for and of learning, but seldom did I find any descriptions that were specific to using the Achievement Chart as the standard lens for engaging in the assessment of student learning itself. My investigation then lead me to the most basic of resources for determining distinction – the dictionary. Well to be honest, I simply Googled it, but these days, that’s pretty much the same thing. So what did I find out? The word think is a verb. It speaks to the process of using one’s mind to reason about something. On the other hand, understanding is a noun. Is speaks to what one comprehends or the insight one has acquired.

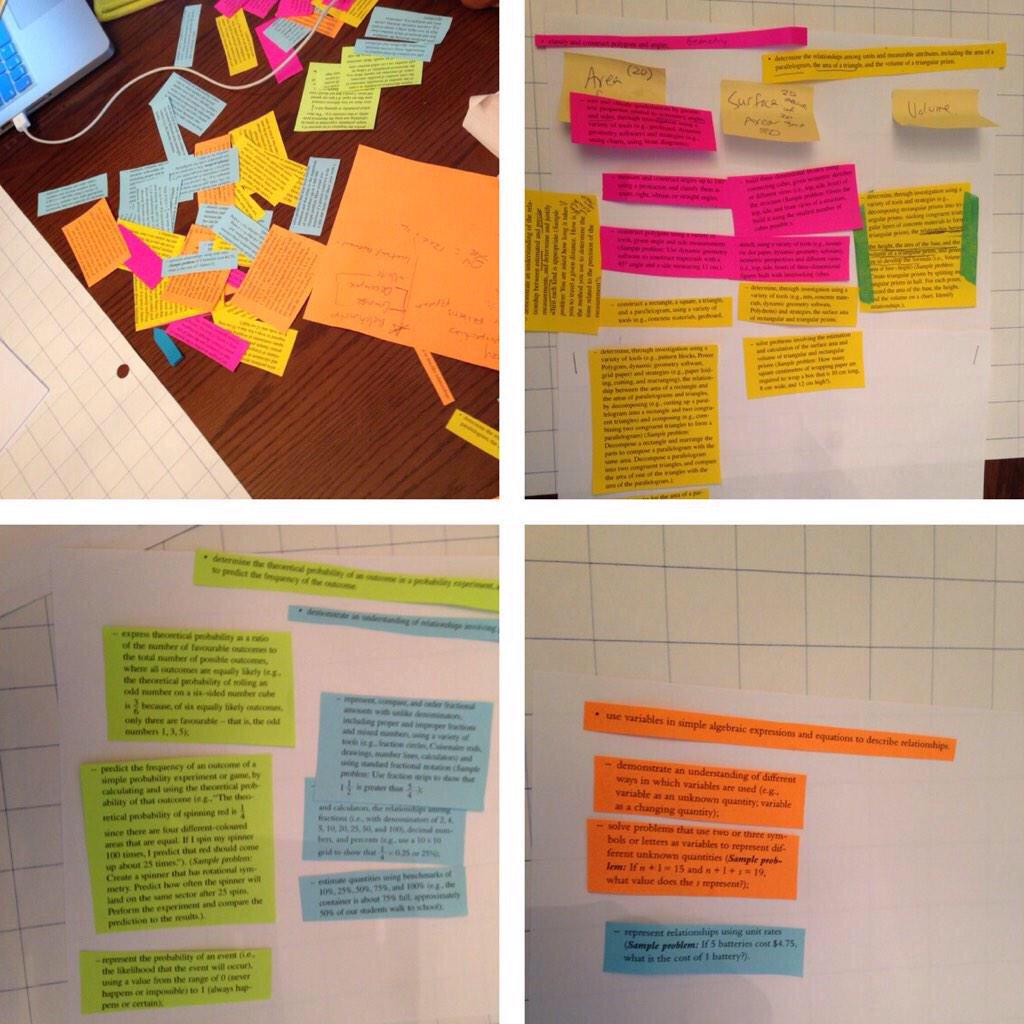

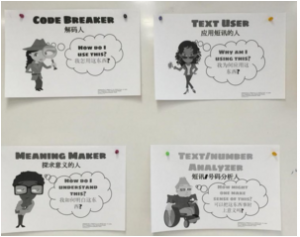

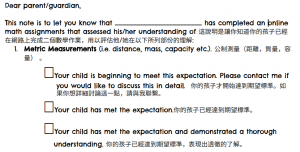

To be fair, simply reading the introduction of any Ontario Curriculum document would immediately highlight this distinction. What I wanted was to first get an unbiased definition that would then be solidified once I referred to the definitions used in the documents. According to the curriculum, language around understanding speaks of having comprehension in subject specific content. Thinking, however, speaks of the uses of planning skills and thinking processes. Eureka! So assessing thinking is actually assessing the process – the series of actions or steps taken. This was the pivotal distinction: The achievement chart calls for teachers to assess the process of thinking and not merely the thought or understanding one arrives at itself.

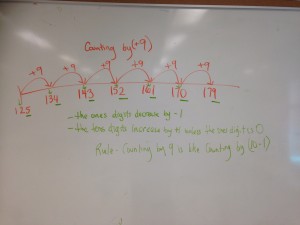

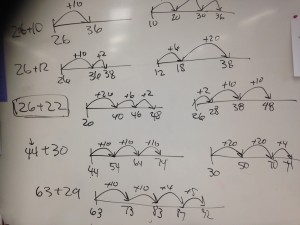

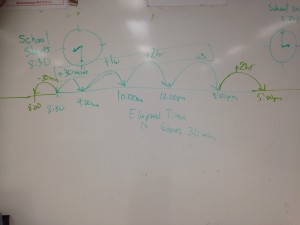

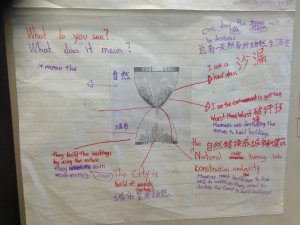

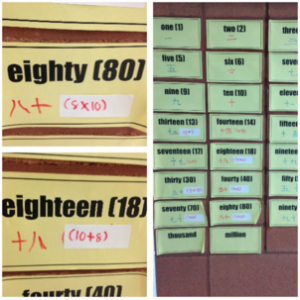

This revelation may not be new, but surely one that we should be reminded about. We are constantly engaging in the assessment process, however, this conversation (or me at least) highlighted the importance of being more intentional and slowing down the thinking process by scaffolding metacognition. By doing so, students can be more aware of their own thinking when it is happening and demonstrate the process they’ve engaged with when they arrive at their own understanding. This also reminded me of the importance to focus on process as well as product when assessing student learning and as such, the importance of actually teaching students a variety of thinking processes (i.e. creative thinking, critical thinking, design thinking, integrative thinking, etc.). What might this actually look like in terms of assessing student thinking? Perhaps it would be focusing on the process students engage with for writing an essay (ie. the writing process) along with the finished process. It might also mean assessing students strategies for problem solving, in addition to the accuracy of their answers. The most important thing to be mindful of is to value the distinction between engaging in thinking and having an understanding. They are not diametrically opposed, but rather are complementary and in knowing so, students can then be invited to see the distinction which will affirm the importance that is placed on both the process and the product.