(This is a story about a student I had several years ago. Her name wasn’t actually Elizabeth. Teaching her taught me a lot about Spec Ed – how to tackle problems in steps, how to work with students to find what works for them individually, and above all else, how incredible it feels to know you really helped someone learn how to be successful.)

I heard about Elizabeth before my job even started. She was one of those students. If you haven’t had one yet, you will: the kids whose reputations precede them. The “hard” kids.

Let’s backtrack, shall we?

Fresh out of my teacher education program, I had just accepted a position teaching a full-day kindergarten program at a private child care centre. At that time, the OT lists for my board (OCDSB) weren’t open, so in order to pay the bills and get some money for AQs in the hopes of one day getting into the board, I took this job.

Because this was a child care centre, my class was small: 10 students total, with 2 more transitioning in partway through the year. This was starting to seem like a pretty easy assignment… until we got to Elizabeth.

“Oh, she’s going to give you a run for your money.”

“She’s vicious.”

“Good luck with her, she’s a nasty one.”

Those were all things people actually said to me about this child. A five year old. I have something of a stubborn streak in me, so right then and there I decided I was going to make it my goal to change Elizabeth’s experience at school.

Elizabeth was a bright, articulate girl who loved story time more than anything, needed you to know her opinion on something, and readily shared facts about things like the moon because she was always reading books and learning new things. She loved art, and she really loved success.

In the classroom, however, Elizabeth seemed to act out. It didn’t take long for me to see what other teachers had warned me about: she hit, she threw things, she had a hard time working with her peers, she couldn’t sit through circle without making at least one other student miserable, and she would have meltdowns during seatwork time.

Other teachers had tried positive and negative reinforcement strategies with her, their success limited. Her parents seemed defeated and were obviously reticent to even ask how her day had gone when they picked her up at the end of the day. I couldn’t figure this kid out: she really enjoyed learning, she really enjoyed arriving at school every day, and she loved her peers, so where was her behaviour coming from?

So I asked her. No one had ever asked her why she did these things. After a particularly trying circle time, I took her aside and calmly asked her why she had trouble sitting through circle time without rolling on the floor, taking out books from the shelves, or touching everyone and everything around her.

And at the tender age of five, she said, “Sitting still hurts.” Her tone was serious. She was distressed. “When I sit still for too long it hurts so I move around, but then I hit people and they get mad.”

It was clear that she felt compelled to move, and that asking her to stop moving was having a detrimental effect on her ability to engage with the class. Together, we discussed some strategies to help her through circle time. As a starting point, we tried fidget toys; she was partial to two bits of LEGO which had been put together with a hinge, so she could move the pieces back and forth while she sat and listened. Most of the time, just having that small toy was enough to keep her physical body occupied while she focused mentally on circle time. Some days she needed more than that, and in those times, we had an arrangement where she could get up and walk around the classroom as long as she didn’t play with anything and was still participating.

So that’s what she did. I sat with the rest of the class, going through our daily calendar work, reading stories, singing songs… and she did everything we did, she was just walking around while she did it. When she had something to contribute, she came to the edge of the carpet and raised her hand just like her peers. She waited to be called on. And when she felt she needed to get up and move again, she would show me a peace sign with her hand, I would nod, and off she would go.

These two small strategies completely changed her experience at circle time. After a month of success, we decided together that we would start tackling seat work next. It turned out that seat work was just as simple to “fix”: she just needed breaks where she could get up and move. She would work on her printing/reading for five minutes, go to a centre for a few minutes, come back to her seat work for another five minutes, go back to centres, etc. Some days she was able to get her seat work done all in one shot, other days she needed to break it up repeatedly, but she always finished it. I used a small timer (which I taught her how to operate) so that she could manage this herself.

There were other things I did to help, of course; I tracked her behaviour relentlessly to see what was and wasn’t working, I tried other strategies like an exercise ball to sit on, I worked with her parents to maintain consistent language and discipline between school and home. But the circle time and seat work strategies were really the key.

As Elizabeth’s behaviour in class improved, her relationships with her peers also improved dramatically. Because she wasn’t upsetting them at circle time any more, they were more keen to play with her and call her to join them at centres. Their forgiveness of her past behaviour was total and almost immediate. Even though they had known her for years and had nearly all been hit, pushed, bit, or yelled at by her, they were willing to set that aside and give her another chance.

By our 100th Day Celebration, I wasn’t tracking her behaviour any more because there wasn’t any need. By the end of the school year, all of our strategies were so second nature that I wasn’t even aware of them any more.

I saw her once a few years later when I was working as a daily OT at her elementary school. I said hello, we shared a smile, and off she went with her friends. She seemed to be doing well!

So, what’s the point of all this? I mean, it’s a nice story, sure, and we probably all have a student or ten like this…

1) Identification isn’t everything. Because this was the private system, I didn’t have any specialists to call on and I couldn’t refer her for any assessments to determine whether or not she had an official diagnosis. I could have suggested that her parents get her tested privately, but I was too new to feel that it was my place to make any comments like that. The thing is, even without being “identified” as Spec Ed, I was able to implement several accommodations which ended up helping her immensely. I didn’t need a legal document telling me that she needed to break work into chunks; I just went for it.

Now, as a public school teacher, I do the same thing: from the first day, I put strategies into place based on my students’ needs, even if they don’t have an IEP. If I think it’s going to help, I do it. I still flag students of concern, don’t get me wrong – but I don’t sit around waiting for those flagged students to actually be assessed. There is a LOT you can do while waiting for your concerns to be addressed.

2) Class size is important. I was teaching a full day kindergarten class with ten students. I was managing several other challenges in that class, but because I only had ten students, I was able to give each of my students a significant portion of my time and energy. It was easy to track behaviour and implement strategies because I only had ten students. I can’t imagine trying to identify, address, and follow up on students of concern in a full day kindergarten classroom in our public boards because they have two or three times as many students as I had. This is part of why we are fighting for smaller class sizes in Ontario.

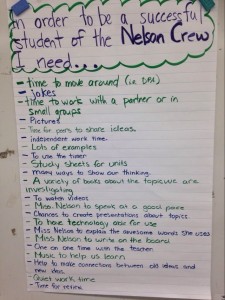

3) Your students can tell you a lot about their needs. We spend a lot of time drawing on our own past experiences, training, and psychology in order to come up with strategies to help our Spec Ed students, but sometimes we forget that sometimes the best source of inspiration is the student him- or herself. I have made it a point, ever since teaching Elizabeth, to work with all of my students (not just the ones with IEPs) and have them identify their strengths and needs. I make them advocate for themselves: if they need to sit closer to the board, or not near their friends, or have a seat totally away from their peers during lessons, then they tell me that and I make it happen. The results have been astonishing and have dramatically reduced the amount of behavioural problems I deal with on a day to day basis.

Make them take ownership of their learning needs. You won’t regret it, I promise. 🙂

math around how many showings of the play we would need to do if we had room for 35 seats in the classroom. We talked about what it would be like if we charged money for the show, what would we use the money for, how much would we get if we charged $0.25 per seat, $1.50 per seat, etc. What if your ticket included popcorn, how much would it cost? We purchased popcorn, popped it and measured how many servings we could get out of it. Then we did the math on how many bags we would need and how much we would need to charge for it. They worked out the math on how long the show was, how much time would be required between showings to get organized again, and then looked at the school schedule to see how many showings they could fit in during the day. They wrote reviews of the play for the newspaper, they wrote ads to go on the announcements, they even filmed commercials! They made a program to hand out, worked out how many copies they would need, they did it all.

math around how many showings of the play we would need to do if we had room for 35 seats in the classroom. We talked about what it would be like if we charged money for the show, what would we use the money for, how much would we get if we charged $0.25 per seat, $1.50 per seat, etc. What if your ticket included popcorn, how much would it cost? We purchased popcorn, popped it and measured how many servings we could get out of it. Then we did the math on how many bags we would need and how much we would need to charge for it. They worked out the math on how long the show was, how much time would be required between showings to get organized again, and then looked at the school schedule to see how many showings they could fit in during the day. They wrote reviews of the play for the newspaper, they wrote ads to go on the announcements, they even filmed commercials! They made a program to hand out, worked out how many copies they would need, they did it all. that was very interested in restaurants. So we incorporated the social studies of food from around the world, and we turned out whole class into a restaurant that served dishes from different places around the world. Again, we did advertising, signage, lots of math around how much we would need of different supplies, etc.

that was very interested in restaurants. So we incorporated the social studies of food from around the world, and we turned out whole class into a restaurant that served dishes from different places around the world. Again, we did advertising, signage, lots of math around how much we would need of different supplies, etc.