Culturally responsive and relevant pedagogy (CRRP) is becoming more and more spoken and written about within teaching and learning communities. In a fast-changing world, educators are challenged to question their own beliefs, values, practices, and pedagogy while remaining in a system that supports and fosters a specific worldview.

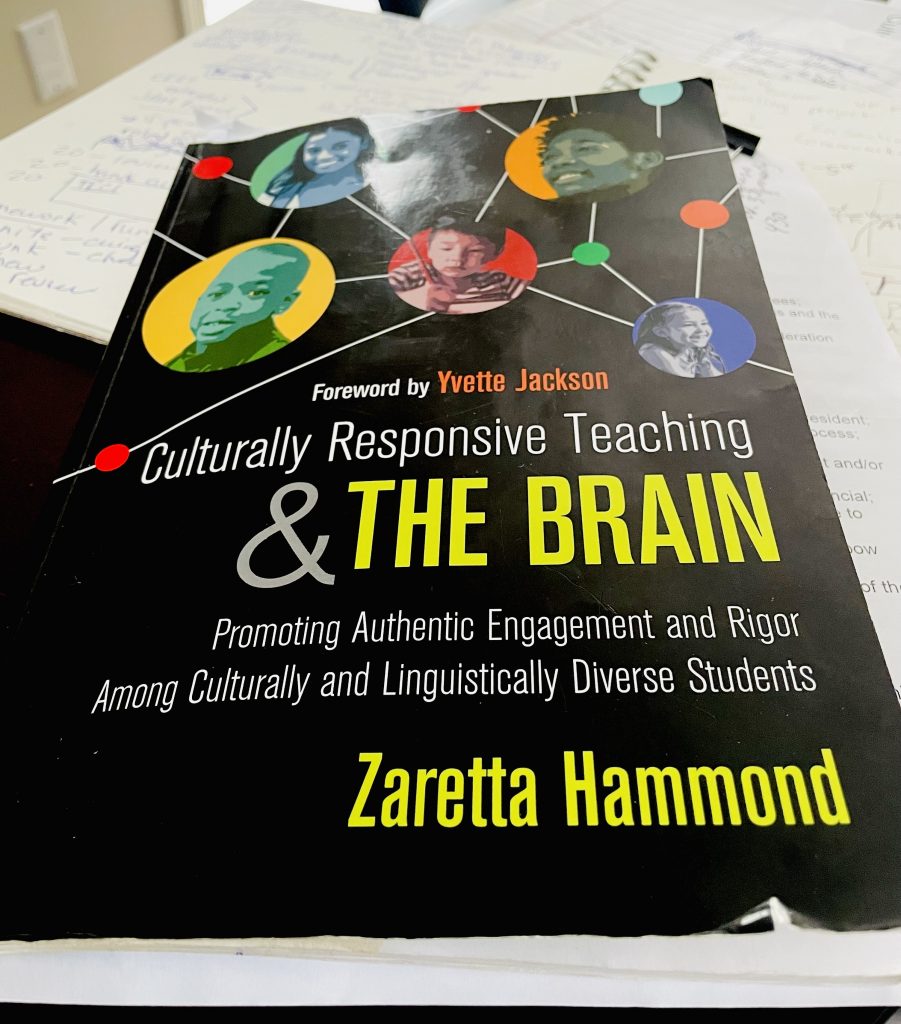

In an effort to connect with like-minded educators who wanted to explore these ideas, I joined an equity, diversity and inclusion focused book club. The book club offered an opportunity for any 20 staff members from the board to receive a copy of the book and engage in monthly discussions of the text. Culturally Responsive Teaching and The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students by Zaretta Hammond is written for educators who want to understand the science and research behind culturally responsive teaching, reflect on their thinking about why we do what we do and challenge the status quo.

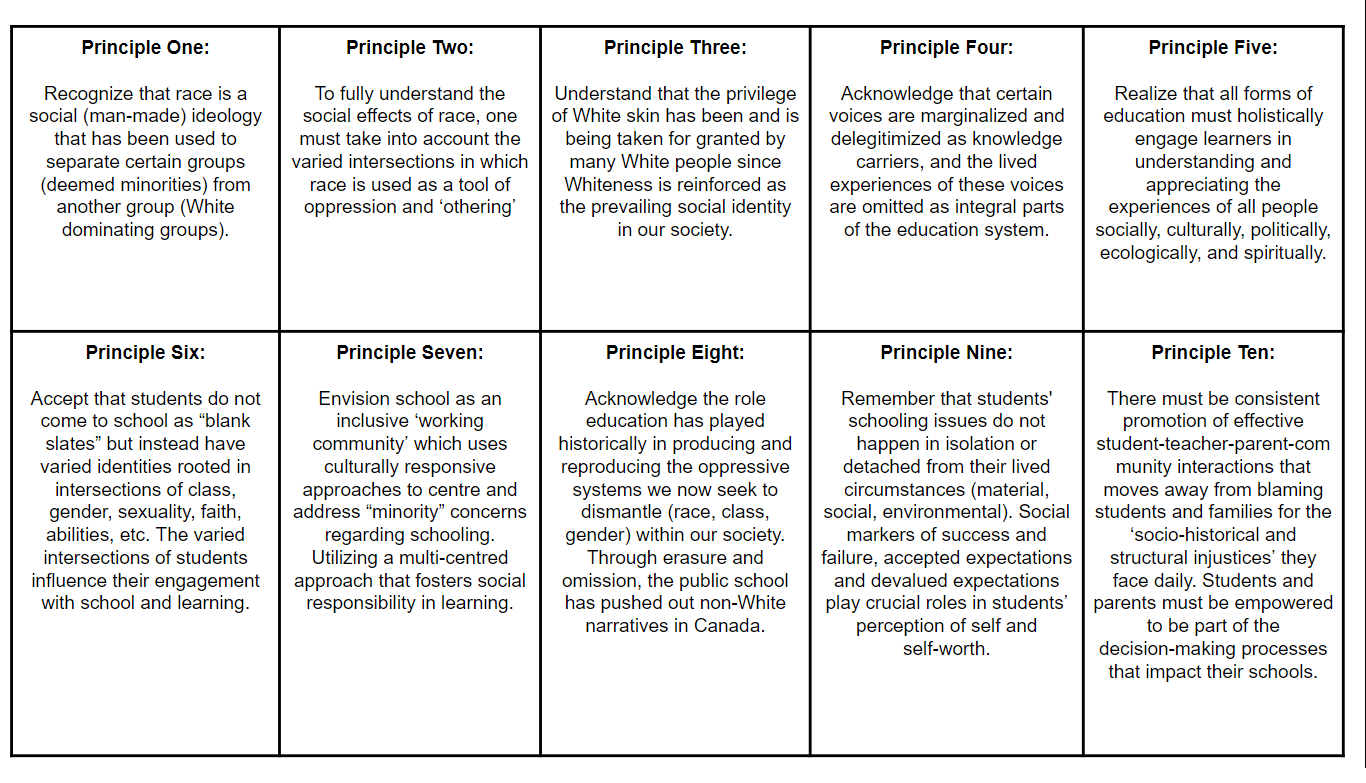

While reading this book, I really appreciated the inclusion of an in-depth explanation of the structural functions of the brain involved in learning and the background knowledge required in order to foster a deep understanding of the role culture plays in learning. Being a reflective teacher, I loved that the author challenged the reader to explore their personal worldviews, core beliefs, and group values and that she described the necessity to go beyond surface (i.e., observable elements such as food and music) and shallow (i.e., social norms such as unspoken rules around personal space or eye contact) levels of culture. This is a concept that resonates with me because many people think of the surface and shallow levels of culture, but to effectively engage in CRRP we need to go beyond that and focus on the roots of culture. As members of an organizational structure I believe it is all of our responsibility to reflect on dominant cultural practices and the explicit and implicit messages these practices convey.

This book assists educators who are ready to dig deep and reflect on their own beliefs and values. In order to understand the worldviews of others, we must first have self-understanding, knowing our own worldview, beliefs and values as well as their origins. Hammond fosters the development of self-understanding by including a set of inquiry questions following each chapter summary. Furthermore, additional resources for further exploration are also included at the end of each chapter. While I did not access these resources yet, they may be useful for additional supportive information as I revisit the text.

Additionally, our book club included educators with different backgrounds and in varying roles and members expressed that some of the concepts were helpful and being utilized in their professional practice. The ideas presented are adaptable for varying grades and the contents of the book suitable for all classroom and school settings. This book would be appealing for any educator ready to rethink traditional teaching practices.

Although some readers may feel the book fails to provide specific examples or lessons, Hammond does a thorough job of creating opportunities for educators to reflect on and shift their mindset about students’ capacities, especially in regards to working with dependent learners. A change in our thinking or expanding our worldview is more valuable to me than a specific lesson plan, and a mindshift fosters CRRP becoming embedded in our practice. Our ever changing classrooms require educators to not only understand the necessity of CRRP within education, but to question the origin of the views, values and beliefs on which our current practices are built. If you are looking for a resource to support your own professional development or that of a group of educators, Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain may be just what you are looking for!

Hammond, Z. L. (2015). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain. Corwin Press.