The role of culturally responsive teaching is to understand who students are as people and who they are within their community. This pedagogical approach acknowledges, responds to, and celebrates fundamental aspects of student culture while providing equitable and inclusive education for students of all backgrounds and identities. This is especially important for students who identify as First Nations, Métis, and/or Inuit (FNMI). Essentially, in teaching through a lens of culturally responsive pedagogy, student identity is honoured.

What is student identity?

Deborah McCallum states identity is “connected to the groups we affiliate with, the language we use, and who we learned the language from. I believe that each of us has various identities according to the different groups that we belong to, and that this has implications in terms of the languages and discourses we use.” (McCallum, November 28, 2017).

Specific characteristics of culturally responsive approaches include educators taking the perspective of :

- positively valuing perspectives of parents and families

- communicating high expectations for all students

- adapting learning within the context of students’ culture, background, and identities

- student-centred instruction and assessment

- considering students’ culture, background, and identities within instruction

- reshaping and adapting curriculum to address students’ cultural and identity issues

- teachers stance as facilitators with students providing input to guide learning

(adapted from Ladson-Billings, 1994)

How does culturally-relevant pedagogy benefit teaching?

Teachers need to be reflective of who their students are and how best to adapt with instruction and assessment to their needs. As reflective practitioners, teachers learn to adapt their teaching to meet the needs of their students. Here, the focus of teaching goes away from the curriculum and towards the learning needs of the students.

Schön (1987) stated that in teachers’ reflection, learning influences behaviour through the teachers’ self-discovery, self- assessment, and deciding the appropriateness of instruction. It is through teacher reflection that the opportunity, the motivation, and the environment reflects on the idea that learning belongs to the learner, the student. In this process, teachers take on the role of and status of facilitator over the traditional role of an “expert” teacher (Schön, 1987).

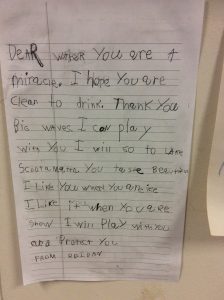

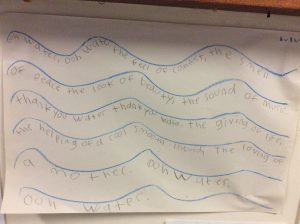

In using a reflective stance (Schön, 1987), teachers incorporate issues of equity, inclusion, and social justice as a necessary element in their day to day teaching practices. The development of culturally relevant teaching strategies is necessary in order to challenge learners to think critically about their own learning and who they are as learners. In other words, to feel included, students need to see themselves within the curriculum and instruction (Hutton, 2019).

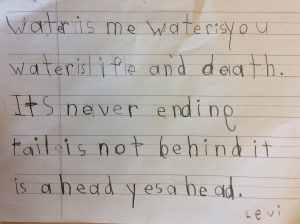

By including their identity in education, students become more engaged in their culture in the context of learning. This helps develop perspective and skills to adapt to present day reality in order to address skills and knowledge for the future (Hutton, 2019).

How does culturally-relevant pedagogy impact families and communities?

It is very important that teachers learn about their students’ families and backgrounds. In learning about the families and communities, students embrace their own understanding of challenges across various cultural communities and backgrounds (Hutton, 2019). This is an importance stance to take given the diversity of students in all Ontario schools.

Developing healthy family-school relationships promotes family involvement and cultural awareness which further develops the supports needed to improve overall student achievement (Epstein, 1995). In addressing the distinctions of families and communities, this results in a varied understanding how families contribute to schools which are part of their community. Depending on language and cultural expectations, different levels of involvement and engagement usually vary (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

Communication between school and home is a critical factor in developing relationships and building overall school capacity. Teachers and families work together to support schools by providing resources and in developing knowledge of diverse learners. Therefore, the community becomes an extension of the community (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

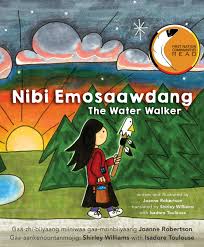

The importance of culturally-relevant pedagogy in teaching First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI) Students

With a history of abuse (i.e. residential schools), assimilation (i.e. absorbing FNMI people into European culture), and neglect (i.e. substandard funding of education and healthcare), educators need to address ways to meet the specific needs of FNMI students in order to increase overall educational achievement (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

Culturally-relevant pedagogy addresses the connection between school and home by promoting communication, forging relationships, and building capacity for all students. At this juncture, teachers and families support diverse learners through local resources and knowledge sharing (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

The importance of culturally-relevant pedagogy in teaching students who do not identify as FNMI

Given the diversity of students across Ontario, classrooms that show diversity of culture need to represent meaningful and relevant depictions of groups of people. Pedagogy should reflect the complexities of cultures, cultural products, and students as individuals. Further, the portrayal of background needs to reflect cultural history and changes that have evolved today which includes the diversity within groups. In other words, students need to identify with curriculum and instruction. Educators must to become more culturally aware in order to meet the needs of their students and the communities where schools stand (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

Understanding student diversity in classrooms and in schools

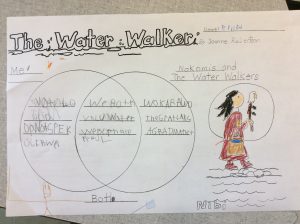

Getting to know students is a powerful approach to help teachers understand who students are and the roots of their family history and culture. In honouring who students are in classrooms and in communities, teachers can adapt instruction and impact engagement in accessing what matters to students in their lives. By moving towards students’ cultural and learning interests, students thrive academically (Ladson-Billings, 1994).

Understanding culturally informed pedagogy in the context of assessment

Teachers undertaking culturally informed pedagogies take on the dual responsibility of external performance of assessment (i.e. large scale government assessments) and building community involvement along with student-driven learning. In balancing the demands of culturally revitalized pedagogy with the demands of present day approaches to assessment, teachers embrace pedagogy that promotes student success by not just propelling FNMI students forward academically … but to also in reclaiming and restoring their cultures (Ladson-Billings, 2014). Ladson-Billings (2014) states that “the real beauty of a culturally sustaining pedagogy is its ability to meet both demands without diminishing ether” (p. 83-84).

Best Practices for Culturally Responsive Teaching & Assessment.

The Culturally Responsive Educator Mindset (adapted from Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014, p. 4 & 5)

- Socio-cultural consciousness: Teachers are aware of how socio-cultural structures impact individual students’ experiences and opportunities towards

- High expectations: Teachers hold positive and affirming views of student success from all backgrounds.

- Desire to make a difference: Teachers work towards more equity and inclusion as change agents.

- Constructivist approach: Teachers understand that students’ learning is constructed through their own knowledge (or schema).

- Deep knowledge of their students: Teachers know who their students are by knowing about students and their families. Teachers then know how individual students learn best and where they are at in their learning.

- Culturally responsive teaching practices: Teachers design and build instruction based on students’ prior knowledge in order to stretch students in their thinking and learning.

Effective Cultural Pedagogy (adapted from Ontario Ministry of Education, 2014, p. 6 & 7)

The quality of teacher instruction and expertise outweighs challenging circumstances that students can bring to the classroom (Callins, 2006; Willis & Harris, 2000). With effective inclusive instruction, there is a promise of high academic rigour within the framework of culturally responsive pedagogy and with the supports to scaffold new learning (Gay, 2002; Ladson-Billings, 2001). Some strategies below were adapted from the work of Kugler and West-Burns (2010):

- Using professional judgement, teachers recognize that curriculum can be expanded upon in informal and the subtle ways in which the curriculum defines what is and what is not valued in students’ schools and society.

- Using inquiry-based approaches to student learning, teachers engaged and self-directed learners. In this approach, students are supported in making decisions about their learning that can integrate who they are and what they already know with their home and community experiences.

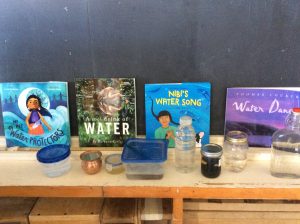

- Using a variety of resources, including community partners, teachers ensure the learning environment and pedagogical materials used are accessible to all learners and that the lives of students and the community are reflected in the daily classroom learning.

- When using resources, materials, and books teachers insure that local and global perspectives are presented and a reflective in the students’ lives.

- Teachers need to know and build upon students’ prior knowledge, interests, strengths and learning styles to ensure they are foundational to the learning experiences in the classroom, in the school, and in the community.

- Teachers need to ensure that learning engages a broad range of learners so that varied perspectives, learning styles, and sources of knowledge are considered.

- When differentiating instruction and ways to demonstrate learning, teachers ensuring both academic rigour and a variety of resources that are accessible to all learners.

- Teachers need to advocate to ensure that the socio-cultural consciousness of students is developed through curricular approaches, emphasizing inclusive and accepting education, to inform an examination and action regarding social justice in education.

Have a restful March Break,

Collaboratively Yours,

Dr. Deb Weston, PhD

References

Callins, T. (2006, Nov./Dec.). Culturally responsive literacy instruction. Teaching Exceptional Children, 62–65.

Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships. Phi delta kappan, 76(9), 701.

Gay, G. (2000). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, practice, & research. New York: Teachers College Press.

Hutton, F. (2019). Notes on culturally responsive pedagogy.

Kugler, J., & West-Burns, N. (2010, Spring). The CUS Framework for Culturally Responsive and Relevant Pedagogy. Our Schools, Our Selves, 19(3).

Ladson-Billings, G. (1994). The dreamkeepers. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishing Co. Downloaded from https://www.brown.edu/academics/education-alliance/teaching-diverse-learners/strategies-0/culturally-responsive-teaching-0#ladson-billings

Ladson-Billings, G. (2001). Crossing over to Canaan: The journey of new teachers in diverse classrooms. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: aka the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74-84.

McCallum, D. (November 28, 2017). Identity and Culturally Responsive Pedagogy , Canadian School Libraries Journal, School Culture, Vol. 1 No. 2, Fall 2017. Downloaded from https://journal.canadianschoollibraries.ca/identity-and-culturally-responsive-pedagogy/

Ontario Ministry of Education. (November 2013). Culturally responsive pedagogy: Towards equity and inclusivity in Ontario Schools, Secretariat Special Edition #35, Ontario Ministry of Education, Downloaded from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/literacynumeracy/inspire/research/cbs_responsivepedagogy.pdf

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner.

Willis, A.I., & Harris, V. (2000). Political acts: Literacy learning and teaching. Reading Research Quarterly, 35(1), 72–88.