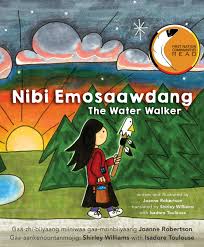

September 30 has been earmarked as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Before this, most educators knew this day as Orange Shirt Day, which stemmed from the story of Phyllis Webstad, a Northern Secwepemc author from the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation, who shares the story of her experiences in a residential school. The significance of September 30 is profound as it calls for us all as a nation, particularly as educators, to pause and reflect on the effects and impact of residential schools on Indigenous peoples (children and adults) to this day. It is estimated that over 150000 Indigenous children attended residential schools in Ontario alone over the span of 100+ years (Restoule, 2013). We know that many of these children did not make it home, while many others still live with the trauma they faced within these schooling systems.

Orange Shirt Day, now known as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, is but a starting point for us as educators. How can we collectively move beyond one day to infuse learning about Indigenous histories and present Indigenous impacts into our overall planning across different subject areas? In the ‘Calls to Action’ reported by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), sections 62 and 63 emphasizes the need for an educational approach that centers Indigenous histories, accounts, and perspectives in the curriculum, not as a one-off event or as an interruption to learning, but instead as an integral part of developing understanding within Canadian education.

Simply put, Indigenous history is Canadian History. Indigenous peoples continue to shape and influence Canadian society in meaningful ways.

“In 2015, ETFO endorsed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action. ETFO understands that it is integral for educators to move forward into reconciliation with the Indigenous Peoples of Canada” (ETFO, 2022). Challenge yourself to learn more using the curated information provided by ETFO, and be intentional about infusing Indigenous representation in the various subject areas you may teach. Resources can be found and explored at etfofnmi.ca

Fostering further development and understanding (both in learning and teaching practices) of Indigenous accounts and narratives in K-12 learning communities not as an alternate focus or ‘alternative learning’, but as a central tenet of Canadian education is critical to moving towards reconciliation as we learn and teach about Indigenous peoples of Canada.

For more exploration and information, visit https://etfofnmi.ca/.

References:

Restoule, K. (2013). An Overview of the Indian Residential School System.’ Anishinabek.ca. Retrieved from https://www.anishinabek.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/An-Overview-of-the-IRS -System-Booklet.pdf.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Reports – NCTR. NCTR – National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation. Retrieved from https://nctr.ca/records/reports/#trc-reports.

Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario. (2015). First Nation, Métis and Inuit (FNMI). Etfo.ca. Retrieved from https://www.etfo.ca/socialjusticeunion/first-nation,-metis-and-inuit-(fnmi).