Last month, my Principal put out a call to the staff at my school: if anyone was interested in participating in a lesson study, she would make it happen. She had briefly filled us in on what a lesson study was at staff meetings, so this was not out of the blue. After debating for a few days, I submitted my name.

A lesson study, for those who aren’t familiar with the term, is a collaborative exercise in professional development and reflective practice. The team creates a lesson together, one teacher delivers the lesson while the others observe the students being taught, and afterward the team discusses their observations. The idea, at least in the case of my school, is to gain insight into how students engage in the lesson and which strategies yield the greatest results for our students. This allows us to reflect on our own practice and see where we can change some things to better help our students succeed.

The response at my school was great. We had enough teachers to run two separate lesson studies, one in Primary and one in Junior. I volunteered my class – a busy, but lovely, group of thirty Grade 4 students – to be taught by another teacher. We planned a lesson related to our School Learning Plan, an annual goal set each year to target our students’ areas of greatest need. Our lesson would teach students about word choice and words with “swagger” (also known as juicy words, to some). We spent half a day setting up the lesson, talking about the students, and deciding which strategies the teacher would focus on using in the classroom.

Two days later, I gave my students a little pep talk, explaining that there would be a teacher delivering a lesson to them while other teachers watched from the sidelines. They thought it was a little weird, but I’m a pretty weird teacher already, so they were ready to roll with it. When the lesson study team arrived, my students got a little weirded out; suddenly there were six adults in the room, including the Principal and their homeroom teacher, and they were clearly feeling like they were under a microscope.

As soon as their teacher – we’ll call her Ms. J – arrived, though, they forgot all about the rest of us. She walked in with spaghetti in her hair (an activation moment for them, as the poem she was reading to kick off the lesson was all about spaghetti) and they immediately needed to know what was happening. She jumped right into the lesson, keeping my students’ attention the entire time. I still don’t know how she did it, but I’m so glad she volunteered to teach the lesson.

While Ms. J was teaching, the rest of us on the team were watching the students, not her. We kept notes on what we noticed – who was fidgeting, who was responding to the strategies Ms. J was using, how the students interpreted the questions being asked, how they interacted with the teacher and each other during the lesson. While the students worked in small groups later in the lesson, we flitted about the room eavesdropping on their conversations, listening to how they interacted with one another. It’s rare that I get to see my students being taught by another teacher, so this opportunity to really focus on them was great.

After the lesson, we had a few hours to chat with each other about our observations. It was interesting to see how we all took notes on very different things, but the take-away from our observations was always the same. That conversation after the teaching was finished was arguably the most beneficial PD that I have had in years. The conclusions we came to, which I’ll mention soon, have had a significant impact on my teaching since participating in this exercise – because we saw just how well the students engaged with and understood the lesson.

So what did we learn?

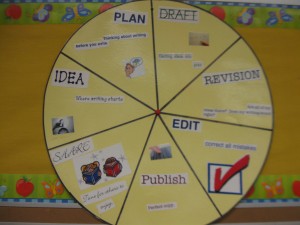

Our biggest take-away was the idea of intentionality. Everything the teacher did in that lesson was intentional, from walking in with spaghetti in her hair, to the poems we chose for group work, to how we built the groups. We had discussed the class beforehand, so she knew which students might have difficulty focusing and she was able to work things into her lesson to grab and keep their attention. Because of the work we put in during the planning phase, there was no wasted time in-class. Everything in the lesson was there for a reason. Being that well-prepared for the lesson meant that during the teaching part, Ms. J was able to adapt on the fly while still sticking to the learning goal.

Another thing we felt was really beneficial was having the learning goal stated explicitly for students at the outset of the lesson. During the lesson, Ms. J would frequently refer back to the stated learning goal any time it seemed like students were drifting off-course. When it came time for them to work in groups, every group knew exactly what to do because they were so in-tune with their goal.

The last thing I want to mention is the idea of letting students engage in the lesson without “judgment”. In order to explain what I mean, I have to give a brief example of what happened in the classroom.

The class had read a poem together as a shared reading exercise. Ms. J then asked them to work with their neighbour and highlight four words in the poem which really stood out – words with “swagger” – and explain why they chose those words. She asked students to come up and highlight the words they had chosen directly on the poem. The first pair of students went fine; they circled a few words, explained their thinking, and returned to their seats. The second pair of students, however, started underlining entire lines of the poem. Ms. J looked for just one brief moment like she was going to stop them, but ultimately she let them finish without comment. In the end, this pair of students underlined four full lines of text, explaining that these four lines summed up the entire poem. As they explained their thinking, it became clear that for them, underlining four words wouldn’t really make the point they wanted to make. They needed all four lines, even though that wasn’t what they were asked to do.

If Ms. J had stopped them and insisted they choose only four words, their entire line of thought would have fallen apart. Instead, she let them do what they had to do without “judging” their response as wrong/a misinterpretation of the task. Because of that, these students were able to demonstrate their learning in a very clear, very comprehensive way. It was a really cool moment, and I suspect it doesn’t come across as well in text. You had to be there.

We learned a lot more than just those three things, of course. We still find ourselves talking about the experience weeks later, finding new things to get excited about and implement in our classrooms. If I get the chance to do another lesson study, I’ll jump on it – and I hope you will, too. It’s a great chance to collaborate with your colleagues and reflect on your practice.

all home and tell their parents about some positive scenario that took place that day. They 100% of the time say an astounding yes. As they come to realize this is a regular part of our classroom, they begin to ask me to call their family and let them know about their math work or reading. That is the time that I know why I will always look to see the glass as half full.

all home and tell their parents about some positive scenario that took place that day. They 100% of the time say an astounding yes. As they come to realize this is a regular part of our classroom, they begin to ask me to call their family and let them know about their math work or reading. That is the time that I know why I will always look to see the glass as half full.