Turned Away: Tale of St. Louis and the fate of its 907 German Jews.

Welcoming Refugees by any other name

While reading the Toronto Star, I came across an article by Martin Regg Cohn writing about his experience meeting refugees making their way through the Vermont forest into Canada. This made me think about black slaves coming to Canada through the Underground Railroad beginning in the late 1700s. This further got me thinking about all the people who have come to Canada seeking refuge after being forced to leave their country in order to escape war, persecution, natural disaster or just to find a secure place to live and raise their family.

Canada (and its previous names of British North America, Upper and Lower Canada, and New France), has always been a destination for refuge. Today and before confederation in 1967, our nation would not have grown in population or diversity without the seekers of refuge. There’s been significant waves of refugee seekers over Canada’s last 250 years. I was surprised at the extend of the list!

This is a partial list from the Government of Canada’s Canada: A History of Refuge

1776: 3,000 Black Loyalists, among them freemen and slaves, fled the oppression of the American Revolution.

1783: Sir Guy Carleton, Governor of the British Province of Quebec, and later to become Lord Dorchester, safely transported 35,000 Loyalist refugees.

1789: Lord Dorchester, Governor-in-Chief of British North America, gave official recognition to the “First Loyalists” – those loyal to the Crown who fled the oppression of the American Revolution to settle in Nova Scotia and Quebec.

1793: Upper Canada became the first province in the British Empire to abolish slavery. In turn, over the course of the 19th century, thousands of black slaves escaped from the United States and came to Canada with the aid of the Underground Railroad, a Christian anti-slavery network.

Late 1700s: Scots Highlanders, refugees of the Highland Clearances during the modernization of Scotland, settled in Canada.

1830: Polish refugees fled to Canada to escape Russian oppression.

1845-1851: Irish refugees escaping the Great Potato Famine.

1880-1914: Italians escaped the ravages of Italy’s unification as farmers were driven off their land as a result of the new Italian state reforms.

1880-1914: Thousands of persecuted Jews, fleeing pogroms in the Pale of Settlement, sought refuge in Canada.

1891: The migration of 170,000 Ukrainians began, mainly to flee oppression from areas under Austro-Hungarian rule, marking the first wave of Ukrainians seeking refuge in Canada. 1920-1939: The second wave of Ukrainians fled from Communism, civil war and Soviet occupation. 1945-1952: The third wave of Ukrainians fled Communist rule.

1947-1952: 250,000 displaced persons (DPs) from Central and Eastern Europe came to Canada, victims of both National Socialism (Nazism) and Communism, and Soviet occupation.

1950s: Canada admitted Palestinian Arabs, driven from their homeland by the Israeli-Arab war of 1948.

1950s-1970s: A significant influx of Middle Eastern and North African Jews fled to Canada.

1956: 37,000 Hungarians escaped Soviet tyranny and found refuge in Canada.

1960s: Chinese refugees fled the Communist violence of the Cultural Revolution.

1968-1969: 11,000 Czech refugees fled the Soviet and Warsaw Pact Communist invasion.

1970s: 7,000 Chilean and other Latin American refugees were allowed to stay in Canada after the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s government in 1973.

1970-1990: Deprived of political and religious freedom, 20,000 Soviet Jews settled in Canada.

1971: After decades of being denied adequate political representation in the central Pakistani government, thousands of Bengali Muslims came to Canada at the outbreak of the Bangladesh Liberation War.

1971-1972: Canada admitted some 228 Tibetans. These refugees, along with their fellow countrymen, were fleeing their homeland after China occupied it in 1959.

1972-1973: Following Idi Amin’s expulsion of Ugandan Asians, 7,000 Ismaili Muslims fled and were brought to Canada.

1979 -1980: More than 60,000 Boat People found refuge in Canada after the Communist victory in the Vietnam War.

1980s: Khmer Cambodians, victims of the Communist regime and the aftershocks of Communist victory in the Vietnam War, fled to Canada.

1990s: By the 1990s, asylum seekers came to Canada from all over the world, particularly Latin America, Eastern Europe and Africa.

1992: 5,000 Bosnian Muslims were admitted to Canada to escape the ethnic cleansing in the Yugoslav Civil War.

1999: Canada airlifted more than 5,000 Kosovars, most of whom were Muslim, to safety.

2006: Canada resettled over 3,900 Karen refugees from refugee camps in Thailand.

2008: Canada began the process of resettling more than 5,000 Bhutanese refugees over five years.

2015: Close to 6,600 Bhutanese refugees arrived in Canada. Canada completes a seven-year commitment and welcomes more than 23,000 Iraqi refugees. Canada commits to and begins resettling 25,000 Syrian refugees.

2017: Canada announces historical increases in multiyear resettled refugee admissions targets, as well as new commitments for resettling refugees from Africa and the Middle-East.

2018: Canada resettled more than 1,300 survivors of Daesh in 2017 and 2018.

If it were not for Canada’s generosity to refugees and immigrants, my mother’s family would not have made it to Canada. Her family consists of Scots Highlanders escaping the Highland Clearance in 1830, British Loyalists and Quakers refusing to participate in the War of 1812, and Irish refugee escaping the starvation of the Potato Famine between 1845-1851. My Northern Irish immigrant father, on the other hand, was escaping bad business deals.

Canada, as a place, has not always been generous to refugees. In 1939, the William Lyon Mackenzie King government turned away 900 Jews escaping Nazis rule in order “to keep this part of the continent free from unrest and from too great an intermixture of foreign strains of blood” (Prime Minister King, 1939). Note that a third of these Jewish refugees died in concentration camps. During World War 2, Canada allowed less than 5,000 Jews into the country – a small quantity considering the numbers for the United States (200,000), Great Britain (195,000), Argentina (50,000), and Brazil (27,000) welcoming Jews into their countries.

In what we now call Canada, British governments created their own refugees through the expulsion of the thriving community of Acadians in 1755 and the ongoing expulsion of indigenous peoples from their traditional lands.

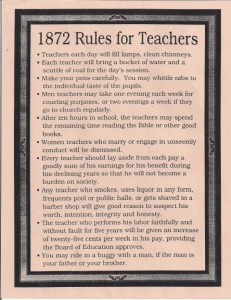

Be aware, that once settled in Canada, people were not safe from human rights violations. In 1941, 22,000 Japanese Canadians were interned in camps along with 660 Germans and 480 Italians. My very intelligent mother-in-law lost her opportunity to complete her high school education after being interned in Lemon Creek, B.C. Many of the internees were born in Canada but were treated as foreigners. The Chinese, who’s hands build Canada’s first national railroad, paid a Chinese only Head Tax for every person entering Canada between 1885 and 1923.

Given its history of welcoming refugees, why is there such a great debate about the current refugee crisis in Canada? If I look at the past refugees and immigrants, a great deal of immigrants could be classified as WASP – White Anglo Saxon Protestants who spoke English. Canada has opened its doors for non British, non English or French speaking refugees and immigrants. In the early 1950s, Canada welcomed my children’s grandparents from Yugoslavia. All the families and relatives lived in one house until each family could afford to buy their own house (this is not unlike what some families do today). The Yugoslavians did not speak English, but they were White.

As classroom teachers, we know who is coming into our country as it is evident from our classroom compositions. I often share that if it were not for refugees and immigrants, I would not have a job as a teacher. I have taught many refugees from all over the world including Africa, Bosnia, Kosovo, Thailand, Syria, Iraq and the Middle East. I have been honoured to teach them and to hear their stories.

I believe that the current refugees are receiving pushback from some Canadians (i.e. who’s families were also immigrants and refugees) because many of the refugees coming to Canada are not White. I believe that this pushback is solely due to racism.

Refugees and immigrants, regardless of place, time, or label, sacrifice everything for a chance at a better life when they set foot in Canada. When talking about human rights in my classroom, I always remind my students that if we do not stand up for the human rights of others, ours could be at risk.

If Canadians allow for the discrimination against our current refugees, we are setting ourselves up for a future of more discrimination, regardless of status in Canada. Do Canadians really want to repeat the tale of the St. Louis and the fate of its 907 German Jews? More recently, do Canadians want to see more children like 3 year old Syrian-Kurdish Alan Kurdi lose their lives while their families seek more secure places to live?

This blog is dedicated to the refugees I had the honour to support as a Red Cross volunteer this summer. I wish you all success in your new country, Canada.

Collaboratively Yours,

Deb Weston

References

https://www.thestar.com/opinion/star-columnists/2018/08/20/my-border-encounter-with-a-migrant-family.html

https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/canada-role/timeline.html

http://thechronicleherald.ca/novascotia/1174272-canada-turned-away-jewish-refugees

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_head_tax_in_Canada

https://www.dummies.com/education/history/world-history/canadian-history-for-dummies-cheat-sheet/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Death_of_Alan_Kurdi