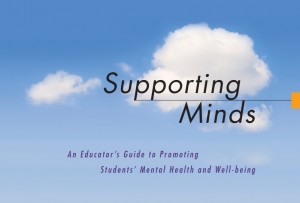

An Educator’s Guide to Promoting Students’ Mental Health and Well-being

Government of Ontario Draft 2013

Note that dealing with mental health problems among students is highly complex and challenging. Often students are not responsive to using mindfulness and self-regulation strategies as their significant mental health needs require the support of professionals such as doctors, psychologists, and therapists. Educators cannot diagnose mental health issues.

As stated below, educators can support their students by observing and documenting possible triggers and behaviours.

How to Use Supporting Minds Document

The Supporting Minds document is presented in two parts.

Part One provides an overview of mental health and addiction problems and guidance about the role of educators in supporting students’ mental health and well-being.

Part Two contains eight sections, each dedicated to a particular mental health problem. Each section is structured to first provide educators the information they need to recognize mental health problems in their students and offer appropriate support (under such headings as “What Is Depression?”, “What Do Symptoms of Depression Look Like?”, and “What Can Educators Do?”). Background information about the particular type of mental health problem is given towards the end of each section. Hyperlinks to resources that provide more detailed information are included throughout.

Please refer to the Supporting Minds document for more in depth information.

Knowing Your Students

A first step in recognizing whether a student has a mental health problem may be simply documenting the behaviour that is causing concern. School boards may have their own forms on which to record this information. Once several observations of the particular behaviour have been gathered, educators can share these with others who can help to develop a plan to manage the behaviour.

Educators should look for three things when considering whether a student is struggling with a mental health and/or addiction problem:

- Frequency: How often does the student exhibit the behaviour?

- Duration: How long does the behaviour last?

- Intensity: To what extent does the behaviour interfere with the student’s social and academic functioning?

Highlighted Mental Health Challenges

1. Anxiety in Students

COMMON SIGNS OF ANXIETY

Although different signs of anxiety occur at different ages, in general, common signs include the following. The student:

- has frequent absences from school;

- asks to be excused from making presentations in class;

- shows a decline in grades;

- is unable to work to expectations;

- refuses to join or participate in social activities;

- avoids school events or parties;

- exhibits panicky crying or freezing tantrums and/or clingy behaviour before or after an activity or social situation (e.g., recess, a class activity);

- worries constantly before an event or activity, asking questions such as “What if …?” without feeling reassured by the answers;

- often spends time alone, or has few friends;

- has great difficulty making friends;

- has physical complaints (e.g., stomach-aches) that are not clearly attributable to a physical health condition;

- worries excessively about things like homework or grades or everyday routines;

- has frequent bouts of tears;

- is easily frustrated;

- is extremely quiet or shy;

- fears new situations;

- avoids social situations for fear of negative evaluations by others (e.g., fear of being laughed at);

- has dysfunctional social behaviours;

- is rejected by peers.

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d.) Note: This list provides some examples but is not exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

STRATEGIES TO REDUCE STRESS FOR ALL STUDENTS

- Create a learning environment where mistakes are viewed as a natural part of the learning process.

- Provide predictable schedules and routines in the classroom.

- Provide advance warning of changes in routine.

- Provide simple relaxation exercises that involve the whole class.

- Encourage students to take small steps towards accomplishing a feared task.

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d.)

See Supporting Minds document Table 1.1 for Specific strategies for supporting students with anxiety-related symptoms

2. Depression in Students

COMMON SIGNS OF DEPRESSION

Some common signs associated with depression include the following:

- ongoing sadness

- irritable or cranky mood

- annoyance about or overreaction to minor difficulties or disappointments

- loss of interest/pleasure in activities that the student normally enjoys

- feelings of hopelessness

- fatigue/lack of energy

- low self-esteem or a negative self-image

- feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- difficulty thinking, concentrating, making decisions, or remembering

- difficulty completing tasks (e.g., homework)

- difficulty commencing tasks and staying on task, or refusal to attempt tasks

- defiant or disruptive behaviour; getting into arguments

- disproportionate worry over little things

- feelings of being agitated or angry

- restlessness; behaviour that is distracting to other students

- negative talk about the future

- excessive crying over relatively small things

- frequent complaints of aches and pains (e.g., stomach-aches and headaches)

- spending time alone/reduced social interaction; withdrawn behaviour and difficulty sustaining friendships

- remaining in the back of the classroom and not participating

- refusal to do school work, and general non-compliance with rules

- negative responses to questions about not working (e.g., “I don’t know”; “It’s not important”; “No one cares, anyway”)

- arriving late or skipping school; irregular attendance

- declining marks

- suicidal thoughts, attempts, or acts

- change in appetite

- loss of weight or increase in weight

- difficulty sleeping (e.g., getting to sleep, staying asleep)

(Based on information from: Calear, 2012; CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; APA, 2000; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d.) Note: This list provides some examples of symptoms or signs but is not exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

STRATEGIES THAT CAN HELP ALL STUDENTS DEVELOP AND MAINTAIN A POSITIVE OUTLOOK

- Support class-wide use of coping strategies and problem-solving skills.

- Provide all students with information about normal growth and development and ways to cope with stress (e.g., ways to address peer pressure, build friendships, address depressive feelings, maintain good sleep hygiene, build exercise into each day).

- Write instructions on the board to provide a visual cue for students who are having trouble focusing on spoken information.

- Model and teach optimistic and positive attitudes, language, and actions.

- Work with students’ strengths and build on them when they complete activities in class.

- Provide students with responsibilities and tasks that they may enjoy (e.g., allow students who enjoy computer use to incorporate a computing component into tasks; allow art-loving students to choose illustrated reading materials).

- Provide a space in the classroom for students to go to when they are feeling overwhelmed.

- Help students to chunk assignments and prepare for tests well in advance of deadlines.

(Based on information from: Evans et al., 2002; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d.)

See Supporting Minds document Table 2.1 for Specific strategies for supporting students with depression-related symptoms

3. Bipolar Disorder in Students

COMMON SIGNS OF BIPOLAR DISORDER

Some common signs to watch for include the following:

- extremely abnormal mood states (generally lasting weeks or more) and involving a depressed or manic mood

- depressive symptoms (see the section on depression)

- manic symptoms, including:

- feeling extraordinarily self-confident, in a manner that is out of character for the student

- extreme irritability or changeable, “up and down” (labile) moods that are not typical for the student

- grandiose and illogical ideas about personal abilities (e.g., the student believes he/she has supernatural powers)

- extremely impaired judgement compared to usual ability

- a perception that thoughts are racing

- extreme changes in speech, particularly very fast speech or talking as if he/she can’t get the words out fast enough

- explosive, lengthy, and often destructive rages that are out of character for the student

- new or marked hyperactivity, agitation, and distractibility

- “dare-devil”, risk-taking behaviour

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011) Note: This list provides some examples but is not exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

In addition, the cognitive functioning of students with diagnosed bipolar disorder may be affected, so that they have difficulty:

- paying attention;

- remembering and recalling information;

- using problem-solving skills;

- using critical thinking skills and categorizing and organizing information;

- quickly coordinating eye-hand movements;

- staying focused on a topic.

See Supporting Minds document Table 2.2 for Specific strategies for supporting students diagnosed with bipolar disorder

4. Students with Attention and Hyperactivity and/or Impulsivity Problems

SUBTYPES OF Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

The following three subtypes of ADHD have been identified:

(1) predominantly inattentive (without symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity)

(2) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive (without symptoms of inattention)

(3) predominantly combined (symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity/ impulsivity)

(Eiraldi et al., 2012). The combined type (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity) is the most common of the three. (Based on information from: APA, 2000)

COMMON SIGNS OF ATTENTION DISORDERS

Some common signs of attention problems and/or hyperactivity/impulsivity include the following:

Attention problems: The student:

- is easily distracted;

- fails to pay attention to details and makes careless mistakes;

- forgets things (e.g., pencils) that are needed to complete a task;

- loses things often;

- has difficulty organizing tasks;

- finds it hard to concentrate;

- follows directions incompletely or improperly;

- frequently doesn’t finish tasks;

- does not listen to what is being said when spoken to;

- avoids or shows strong dislike for schoolwork or homework that requires sustained mental effort (dedicated thinking).

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; APA, 2000; CAMH, 2007)

Hyperactivity/Impulsivity: The student:

- has difficulty sitting still or remaining in seat;

- fidgets;

- has difficulty staying in one place;

- talks excessively or all the time;

- is overly active, which may disturb peers or family members;

- has difficulty playing quietly;

- is always on the move;

- has feelings of restlessness (for adolescents);

- is unable to suppress impulses such as making inappropriate comments;

- interrupts conversations;

- shouts out answers before the end of the question or without being called on;

- hits others;

- has difficulty waiting for a turn;

- is easily frustrated;

- displays poor judgement.

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; APA, 2000; CAMH, 2007) Note: This list provides some examples but is not exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

STRATEGIES THAT PROMOTE A CALM CLASSROOM ATMOSPHERE TO HELP ALL STUDENTS PAY ATTENTION

- Provide a structured environment and a consistent daily routine.

- Provide advance warning of changes in routines or activities.

- Establish a routine and set of rules for moving from one activity to the next.

- Establish procedures that allow all students equal opportunities to participate in activities (e.g., establish rules for turn taking; arrange for everyone to get a chance to be first).

- Provide easy-to-follow directions and instructions (e.g., explain one step at a time; chunk multi-step directions).

- Post rules where everyone can see them.

- Reinforce positive behaviour such as raising a hand before speaking, engaging in quiet work.

- Provide opportunities to learn by doing to give students an outlet for excess energy.

- Limit visual and auditory distractions in the classroom as much as possible while considering the needs of all students.

- When talking to students, address them directly and use eye contact. Wait until a student is paying attention before continuing a conversation.

- Avoid a focus on competition, as students’ urge to win or be first can increase the likelihood of impulsive behaviour.

(Based on information from: House, 2002; CAMH, 2007)

See Supporting Minds document Table 3.1 for Specific strategies for supporting students with attention and hyperactivity/impulsivity problem

5. Behaviour Disorder in Students

COMMON SIGNS OF BEHAVIOUR DISORDERS

Some common indicators of problem behaviour include the following:

- defiance (persistent stubbornness; resistance to following directions; unwillingness to compromise, give in, or negotiate)

- persistent testing of limits (by ignoring, arguing, not accepting blame)

- persistent hostile mood

- lack of empathy, guilt, or remorse, and a tendency to blame others for his/her own mistakes

- low self-esteem that may masquerade as “toughness”

- acting aggressively

- disobedience

- oppositional behaviour (e.g., challenging or arguing with authority figures)

- bullying, threatening, or intimidating others

- initiating fights or displaying physical violence/cruelty

- using weapons

- stealing

- deliberate destruction of property

- frequent lying

- serious violations of rules (e.g., in early adolescents, staying out late when forbidden to do so)

- skipping school often

- outbursts of anger, low tolerance for frustration, irritability

- recklessness; risk-taking acts

Signs that the problem may be serious include the following:

- The student shows problems with behaviour for several months, is repeatedly disobedient, talks back, or is physically aggressive.

- The behaviour is out of the ordinary and is a serious violation of the accepted rules in the family and community (e.g., vandalism, theft, violence).

- The behaviour goes far beyond childish mischief or adolescent rebelliousness.

- The behaviour is not simply a reaction to something stressful that is happening in the student’s life (e.g., widespread crime in the community, poverty).

(Based on information from: APA, 2000; CPRF, 2005; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d.) Note: These lists provide some examples but are not exhaustive and should not be used for diagnostic purposes.

STRATEGIES THAT PROMOTE POSITIVE BEHAVIOUR AMONG ALL STUDENTS

- Provide predictable schedules and routines in the classroom.

- Focus the students’ attention before starting the lesson.

- Use direct instruction to clarify what will be happening.

- Model the quiet, respectful behaviour students are expected to demonstrate.

- Create an inviting classroom environment that may include a quiet space, with few distractions, to which a student can retreat.

- Be aware of the range of needs of the students in the class in order to provide an appropriate level of stimulation.

- Communicate expectations clearly and enforce them consistently. Use clear statements when speaking to students: “I expect you to …” or “I want you to…”.

- Focus on appropriate behaviour. Use rules that describe the behaviour you want, not the behaviour you are discouraging (e.g., Instead of saying “No fighting”, say “Settle conflicts appropriately”).

- At the beginning of the school year, clearly and simply define expectations for honesty, responsibility, and accountability at school. Repeat these expectations often to the entire class, especially when violations occur.

- Don’t focus too much attention on children who blame others, since that might inadvertently reinforce the behaviour.

- Begin each day with a clean slate.

- Facilitate the transition from the playground to the classroom by calmly telling students when there are five minutes left and then one minute left in recess, encouraging them to prepare to come in, and helping them settle in class when recess is over. Schedule a predictable classroom activity that most students will enjoy to follow recess, to help provide a smooth transition.

(Based on information from: CYMHIN-MAD, 2011; Hincks-Dellcrest-ABCs, n.d; Lee, 2012)

See document Table 4.1 for Specific strategies for supporting students with behavioural problems in classrooms

Please see the Supporting Minds document for further information on

- Eating and weight-related problems in students

- Substance use problems in students

- Gambling in students

- Self-harm and suicide in students

Taking care of self as an educator

(Supporting Minds, Appendix C: Mental Health Action Signs)

Your behavioural health is an important part of your physical health. If you are experiencing any of these feelings, let your doctor know.

- Feeling very sad or withdrawn for more than 2 weeks

- Seriously trying to harm or kill yourself, or making plans to do so

- Sudden overwhelming fear for no reason, sometimes with a racing heart or fast breathing

- Involvement in many fights, using a weapon, or wanting to badly hurt others

- Severe out-of-control behaviour that can hurt yourself or others

- Not eating, throwing up, or using laxatives to make yourself lose weight

- Intense worries or fears that get in the way of your daily activities

- Extreme difficulty in concentrating or staying still that puts you in physical danger or causes school failure

- Repeated use of drugs or alcohol

- Severe mood swings that cause problems in relationships

- Drastic changes in your behaviour or personality

Source: The Reach Institute, The “Action Signs” Project, p. 6. Retrieved from http://www.thereachinstitute.org/files/documents/action-signs-toolkit-final.pdf

Dealing with students with mental health needs can be very challenging and draining.

Be kind to yourself and practice self care.

Reach out for help and support if you need it.

Collaboratively Yours,

Deb Weston