GLOW (Gay, Lesbian or Whatever) is an extracurricular club for Grades 6-8 students to explore issues related to the 2SLGBTQ+ community and their allies. We have been meeting on-line every week since April 2020. Before COVID-19, we would meet during lunch at school. GLOW is a proud and positive space for students and educators to share their own stories, ask questions, make art, and take action. It is always the highlight of my week.

There is extensive data to hold schools accountable and support students who may identify as 2SLGTBQ+. Many of these students continue to be bullied or harassed by their peers, and pushed out of school. It is critical that educators respond to homophobic or transphobic comments and actions that are harmful, and to teach diverse stories of 2SLGBTQ+ communities with pride. There are several resources provided at the end of this blog.

WHERE DO I BEGIN?

You don’t need permission to start a GSA (Gay-Straight Alliance). In fact, if a student requests a GSA, many schools are required to provide one. The first thing I did was reach out to my Grade 7/8 teacher friend, Tia Chambers. I asked her to share the role with me because everyone needs an ally. It didn’t take long before other staff wanted to join GLOW. This year, we are sharing the role of co-host with Kindergarten teacher, Nikki Kovac.

We start every meeting with an introduction, which includes our pronouns, and we answer a question. This helps us to build relationships and honour who we are. If there is a new member, we will review our GLOW Agreements. These agreements were generated together in our first meeting and describe what we hope for and what we need in order to feel comfortable.

After making our agreements, we invited students to share music that they like and we created a playlist. Some of these songs are performed by 2SLGBTQ+ performers, and other songs just make us feel good. We asked everyone for ideas about what they wanted to discuss, and the type of activities they might want to do. It is important for educators to amplify student voice, listen and respond with respect. Inspired and informed by the students’ ideas and questions, we prepare activities and questions to guide our discussion every week.

WHAT HAPPENS AT GLOW?

Here is an example of what we discussed at our GLOW meetings in February. As Valentine’s Day was approaching, I wanted to challenge the heteronormative narrative about love and romantic relationships that are reinforced by the media, and create space for more possibilities. I thought that we might discuss these issues and create our own Valentine’s Day cards with inclusive messages.

Our check-in question was about love. I asked: “What or Who do you love?” Then, I used these guiding questions: “What are the messages about love and relationships that you notice on television or in movies?” “Who do they include or exclude?” “How do these messages reinforce a “norm” about relationships that is heterosexual?” “How might we make Valentine’s Day more inclusive?” We also talked about self-love and different ways we might care for ourselves.

I shared a few examples of Valentine’s Day cards that provide a counternarrative, and I invited everyone to design their own inclusive Valentines. We talked about word play, and how Valentines often include puns and rhyme. As we drew, we listened to songs on our playlist. The following week, one of the students shared a poem that they had written about love that was inspired by our discussion. It filled my heart with pride.

RESOURCES

ETFO has created many resources to support educators who want to create brave and inclusive spaces in our schools.

My teacher friend, Melissa Major, has written two excellent articles in VOICE magazine, which can spark meaningful discussions with your students:

How to Become a Super Rad Gender Warrior reminds us that all members of a school community have the right:

To be free from discrimination and harassment.

To have a safe and inclusive learning environment.

To use the bathroom or change room they feel is the most appropriate.

To dress in a way that feels right and safe for them.

To be spoken to with their chosen name and gender pronoun.

To be treated with dignity and respect and the recognition that all gender expressions and identities are a normal and healthy part of a spectrum.

To present their gender in different ways at different times

Gender Neutral Language: An Activity for Day of Pink or Any Day explains how educators can use inclusive language to disrupt the gender binary.

Last Spring, I attended an ETFO webinar called “How to start a GSA and support 2SLGBTQ+ during Remote Learning” presented by Toronto teacher, Jordan Applebaum. It was intersectional and inspiring. You can watch the webinar in four parts here:

Be Proactive to Support Trans and LGBTQIA2S POC – Part 1

Be Proactive to Support Trans and LGBTQIA2S POC – Part 2

Be Proactive: How to Start a GSA During Remote Learning – Part 3

Be Proactive: How to Start A GSA During Remote Learning – Part 4

I have also joined a few Facebook groups to support this work. Recently, I discovered that the Durham District School Board has created Pink Shirt Day and Beyond, a slide deck which is filled with lesson plans to use in the classroom or at your next GLOW meeting.

Shine on!!

esented as LGBTQIT. In addition, we discussed LGBTQIT inclusion during the Day of Pink and while discussing human rights topics. I received notes from parents asking me not to talk about same sex couples on the Day of Pink. I also had students missing from school on the Day of Pink. Some parents believed that discussions of inclusion were only limited to specific school days. Parents needed to realize that teachers talk about inclusion, as needed, especially when students rights are being suppressed. Inclusion is not limited to skin colour, culture, religion, chosen head coverings, ethnicity, ancestry, citizenship, disability, or diet.

esented as LGBTQIT. In addition, we discussed LGBTQIT inclusion during the Day of Pink and while discussing human rights topics. I received notes from parents asking me not to talk about same sex couples on the Day of Pink. I also had students missing from school on the Day of Pink. Some parents believed that discussions of inclusion were only limited to specific school days. Parents needed to realize that teachers talk about inclusion, as needed, especially when students rights are being suppressed. Inclusion is not limited to skin colour, culture, religion, chosen head coverings, ethnicity, ancestry, citizenship, disability, or diet.

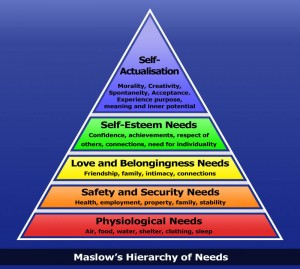

does not get enough attention. I’m talking about mental health in schools.

does not get enough attention. I’m talking about mental health in schools.