Violence in the classroom is emerging as a significant issue for teachers’ working conditions and students’ learning conditions.

In the United States, a national survey of 2998 teachers from 48 states noted that 80% of teachers reported at least one incidence of violence with 94% of respondents stating students as the source (McMahon, Martinez, Espelage, Rose, Reddy, Lane, & Brown, 2014). In another US study, 2324 teachers reported at least one occurrence of student generated violence against teachers. These incidences where not consistently reported even with teachers experiencing multiple occurrences. This was especially significant when there was a lack of administrative support (Martinez, McMhan, Espelage, Anderman, Reddy & Sabchez, 2016). Several authors noted an increase in students’ aggressive behaviour shifting to ever lower age brackets including those students in Kindergarten (Emmerová, 2014; Kirves & Sajaniemi, 2012).

Emerging Trends in the Media

The media has also highlighted the emerging trend of increases in students’ aggressive behaviour. In February of 2019, CBC Radio’s The Sunday Edition posted a commentary, “I felt helpless”: Teachers call for support amid escalating crisis’ of classroom violence, summarizing a teacher’s reluctance to report violence in schools over “fear of repercussions”. Sherri Brown, director of research and professional learning at the Canadian Teachers’ Federation (CTF), described the current state as an “escalating crisis” and also noted that much violence in the classroom goes under reported.

In 2018, a national organization compiled the results of a survey conducted by Elementary Teachers Federation (ETFO) showing that of its 81,000 members, 70% of elementary teachers reported experiencing or witnessing violence at their school workplace during the 2016-17 school year. In addition, the survey results noted that 80% of ETFO members noticed an increase in school based violence and 75% of ETFO members reported school based violence becoming more severe.

The People for Education’s Annual Report (2017) stated that principals reported significant increases in students’ mental health needs and behavioural issues. Principals stated that mental health issues were taking an increasing amount of their time and that schools had inadequate levels of support from social workers, psychologists, and guidance counsellors. The report went further highlighting that “in 2017, 47% of Ontario elementary schools reported having no access to child and youth workers, 15% did not have access to social workers, and 13% did not have access to psychologists.” People for Education also addressed the increased importance of social and emotional development for students which included self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, interpersonal relations, and decision making.

At this point, I’ll state my concerns about the response of Ontario school boards in advocating for students using self-regulation and mindfulness strategies in order to address the increases in behavioural needs. Self-regulation and mindfulness strategies do help some students develop their social and emotional capacity but self-regulation and mindfulness strategies do not compensate for the myriad of causes and complex intersectionality of environmental, developmental, intellectual, social, emotional, economic, and mental health needs that may be at the root of students’ behavioural outcomes. Students’ behaviour needs have complex and multi-causal roots. Using mindfulness strategies as a treatment to these significant student behavioural issues is like putting a bandage on a gushing wound.

Violence against teachers significantly impacts classroom and school cultures. When students become verbally or physically aggressive against their teachers, this creates an unsafe environment for learning. A teacher’s job is not just to teach students, their job is to also keep their students safe. When the teacher, who is the adult that keeps students safe, is dealing with aggressive student behaviour, the other students do not feel safe. Further, aggressive behaviour interrupts learning and wastes valuable classroom time.

When dealing with aggressive behaviour, teachers have many options. Often teachers ignore aggressive behaviour to disengage the offending student. The next step in disarming student behaviour includes removing the student from the classroom, contacting administrators, and contacting parents. Even with these steps, students often continue with their behaviour. Parents may or may not engage teachers in their outreach for support. Based on personal experience, when parents hold their children accountable, student behaviour often improves. But when parents do not hold their children accountable and blame the teacher for the behaviour, students often continue forward, sometimes escalating in their actions. When aggressive behaviour significantly escalates, teachers must act to protect their students and themselves from harm.

Disciplinary actions are often a result of continuous issues with students’ behaviour and are administered by school principals. Here, progressive discipline comes into play. The approach of progressive discipline is to provide a continuum of interventions, supports, and consequences that are clear and developmentally appropriate in order to reinforce positive behaviours and help students succeed in school. Interventions include verbal reminders, contact with parents, withdrawal of privileges, referral to counselling, and possible suspension and/or expulsion. Within the context of disciplinary actions, the student’s Individual Education Plan (IEP) is also considered. As part of the student’s IEP a Safety Plan and a Positive Behaviour Intervention Plan (PBIP) may also be in place.

There is a list of activities that can lead to suspension which include uttering threats of bodily harm on another person, swearing at a teacher or a person of authority, bullying/cyberbullying and any other activities identified in school boards’ policies (i.e. Safe Schools). Principals must consider a number of factors before deciding upon a suspension including students’ age, cognitive ability, social/emotional history, special education needs, and ongoing education.

The challenge with progressive discipline is that students’ circumstances may dictate no suspension and instead initiate a need for increased student support. The challenge with obtaining increased support for students with behaviour needs is that there is inadequate funding to provide this support. Without support to deal with significant aggressive behaviour, students return to their classrooms and the teachers must deal with future aggressive behaviours (see Suspension and Expulsion: What parents need to know.)

Violence tends to be underreported in schools for many reasons including a lack of adequate reporting venues, a lack of time to complete requirements for reporting, a fear of reprisals from administration, and a lack of understanding of the seriousness of the behaviour upon which it should have been documented before it escalated (one in which I have been complicit).

Putting Students’ Aggressive Behaviour into Real Life Context.

In the late spring of 2019, the Occupational Health Clinics for Ontario Workers Inc. (OHCOW) conducted a survey to measure the psychosocial factors of elementary teacher members in Ontario. This survey was based on the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire which was developed as part of a survey of the psychosocial work environment among Danish employees. Specifically, this survey used the COPSOQ II (Short) and COPSOQ III (Core) surveys with additional survey questions from the Mental Injury Tool (MIT) Group 2017 edition. Various versions of the COPSOQ survey have been translated into many different languages and are used to measure psychosocial factors in workplaces around the world. The survey participants were members of an ETFO teacher local.

Although the survey results are not a direct representation of the population of all members, it can be used to the gage working conditions in this ETFO teacher local. A total of 496 participants accessed the survey and 396 participants completed the survey. This accounts for an approximate response of 6% of the member population for this local. This sample of ETFO members had a variety of teaching assignments including approximately 33% Primary/Kindergarten, 15% Junior, 12% Intermediate, and 12% Physical Education/Health in participant identification. The majority of teacher participants had 16 to 20 years of experience (28%) followed by 24% of participants with 11 to 15 years, 23% over 20 years, and 19% with 6 to 10 years of experience. Over 85% of the survey participants identified as a woman which is slightly over the 81% of ETFO members who identify as a woman. The majority of participants (96%) worked full time.

In addressing issues regarding offensive behaviour, the participants indicated:

- 47% experienced threats of violence from students

- 48% experienced physical violence from students

- 17% experienced bullying from students

- 10% experienced discrimination from students

- 86% experienced any offensive behaviour overall

Survey participants showed high levels of burnout with 69% indicating much worse than average Canadian workers as represented by feeling worn out, physically /emotionally exhausted, and tired. Survey participants expressed significant signs of stress, irritability, problems relaxing, and feeling tense with 57% indicating much worse than average Canadian workers. Participants indicated challenges with sleeping (46% much worse), somatic symptoms to stress and anxiety (40% much worse), and cognitive/concentration issues (46% much worse).

In measuring workplace their Psychological Health and Safety climate, participants indicated it was not so good (25%), poor (21%), or toxic (13%). Further, participants agreed (37%) or strongly agreed (28%) that their board’s organizational culture tolerated behaviours harmful to mental health. Participants disagreed (38%) or strongly disagreed (25%) that their board had enough resources and disagreed (43%) or strongly disagreed (36%) that there was adequate staffing. A total of 44% of participants never or hardly ever felt comfortable discussing workload issues with their immediate supervisor. Finally, when asked about the effectiveness of their board’s violence and harassment policies, 42% disagreed or strongly disagreed that these policies were effective.

In this survey, it is not surprising that these teachers were experiencing signs of stress and burnout – given that the participants showed that they were dealing with significant levels of students’ offensive behaviour in a climate with poor psychological health and safety supports. This paints a picture of teachers’ poor working conditions as they were dealing with inadequate resources and staffing to support teachers. And I posit that poor working conditions for teachers result in poor learning conditions for students.

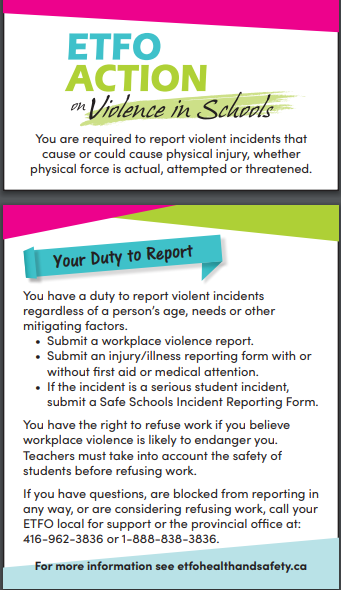

Under the Workplace violence under the Occupational Health and Safety Act workplace violence is clearly outlined. Further, the Workplace violence in school boards: A guide to the law outlines specifics on how to deal with violence in schools.

Teachers should not have to deal with workplace violence issues as part of their job. But it is becoming a commonplace occurrence in Ontario classrooms. In the 2018/2019 school year, I personally experienced being bitten, being repeatedly kicked while protecting another student, had items thrown at me, being sworn at, had my personal property damaged and destroyed, and being threatened with being stabbed and killed with a knife. All of this behaviour came from students who were in the primary grades.

I write this blog because I care deeply about the impact violence in schools has on teachers teaching and students learning. I understand what it is like to experience violence from students as I have personal stories to tell.

Below I’ve noted some excellent downloadable resources provided by the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario which may help teachers, like me, deal with violence in their classrooms – I have the poster in my classroom.

As always, Collaboratively Yours,

Dr. Deb Weston, PhD

- A Glossary of Workplace Violence Definitions for ETFO Members

- Brochure – ETFO Action on Violence in Schools

- Poster/Wallet Card – ETFO Action on Violence in Schools

References

Emmerová, I. (2014). Aggressive Behaviour of Pupils against Teachers – Theoretical Reflection and School Practice. The New Educational Review, Vol. 35. No. 2, pp. 147–156.

Kirves, L., & Sajaniemi, N. (2012). Bullying in early educational settings. Early Child Development and Care, 182(3-4), 383-400.

McMahon, S. D., Martinez, A., Espelage, D., Rose, C., Reddy, L. A., Lane, K., & Brown, V. (2014). Violence directed against teachers: Results from a national survey. Psychology in the Schools, 51(7), 753-766.