“If the effort to respect and honour the social reality and experiences of groups in this society who are nonwhite is to be reflected in a pedagogical process, then as teachers – on all levels – we must acknowledge that our styles of teaching may need to change” (Hooks, 1994, p.35).

For every teacher in the classroom, there is another teacher out there who inspired them. As teachers, we often teach as we were taught. We develop our teaching identity and teaching practice based on the teachers we admired growing up or the styles of teaching we witnessed and liked during our time at Teachers College (whether local or international). Unfortunately, many of the teaching styles we emulate are not grounded or founded in anti-oppressive teaching practice since multicultural narratives and diversity of educational perspectives were not the bedrock of learning. This is no longer the case in education. Meaningful learning has been identified as being culturally relevant to learners and responsive in fostering a learning environment that reflects all learners in their diversity. Simply put, do the students see themselves reflected meaningfully in their learning?

“When I first entered the multicultural, multiethnic classroom setting, I was unprepared. I did not know how to cope effectively with so much “difference.” Despite progressive politics and my deep engagement with the feminist movement, I had never before been compelled to work within a truly diverse setting, and I lacked the necessary skills” (Hooks, 1994, p. 41).

To provide context, Bell Hooks was an author, a social activist, and an educator who examined how race, feminism, and class are used as systems of oppression and class domination. She began her career as an educator in 1976 and taught until she passed away in 2018. In her 42-year career as an educator, she emphasized the power that educating from a multi-cultural perspective (a multinarrative) brings to the learning environment.

How dynamic would our classrooms be if we created and fostered space for students to be their authentic selves? How much more engagement would there be if students engaged with learning, not just as something to do, but as a part of who they are?

“The exciting aspect of creating a classroom community where there is respect for individual voices is that there is infinitely more feedback because students do feel free to talk – and talk back” (Hooks, 1994, p. 45). Students see themselves in their learning and recognize that they are part of it.

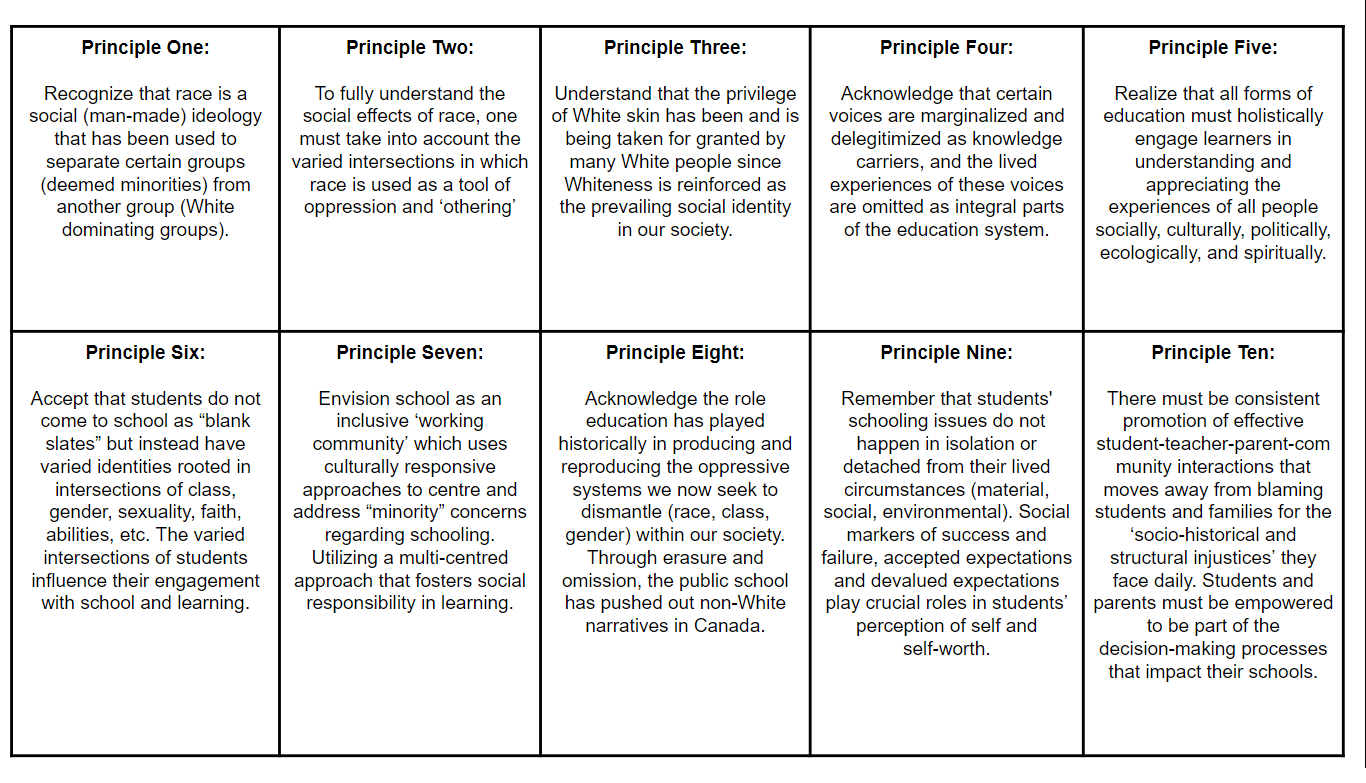

To better understand how this can be fostered in your classroom, it is first important to understand what a multicultural classroom is. “From language barriers to social skills, behaviour to discipline, and classroom involvement to academic performance, multicultural education aims to provide equitable educational opportunities to all students” (CueMath, 2021). The teacher must be intentional about utilizing teaching styles and strategies that remove barriers and eliminate issues that students often face in trying to adopt a single narrative to teaching and learning.

“Regardless of social class, caste, gender, or creed, a multicultural classroom serves all students and nurtures young minds to learn together. It also seeks transparency and acceptance of all cultural identities in a class without bias or partiality” (CueMath, 2021). A teacher who fosters multiculturalism models acceptance of differences, encourages learning beyond a single narrative and always uplifts multiplicity in learning perspectives as they accentuate students’ diverse identities.

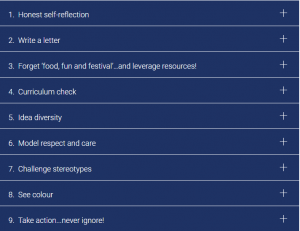

To learn more about how you can create an environment that ‘Teaches to Transgress” and embrace equality and diversity in our ever-changing classroom environments, read through these nine tips that have been provided by OISE Professor Ann Lopez and Richard Messina, Principal of OISE’s Dr. Eric Jackman Institute of Child Study (JICS).

References

Craig, L. (2017, September 7). 9 ways to create an inclusive environment in a diverse classroom. University of Toronto Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Retrieved December 18, 2022, from https://www.oise.utoronto.ca/oise/About_OISE/Dealing_with_diversity_in_the_classroom.html

CueMath. (2021, January 21). Learn about multicultural education and ways to implement. Cuemath. Retrieved December 18, 2022, from https://www.cuemath.com/learn/multicultural-education/

Hooks, B. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York u.a: Routledge.