I was invited to co-host a webinar about Ecojustice Education, hosted by the Toronto District School Board’s EcoSchools team, in collaboration with OISE’s Environmental and Sustainability Education Initiative.

My inspiring co-host was Farah Wadia. Farah is a Grade 7/8 teacher in Toronto, and she has written about her work raising issues of environmental justice through the study of water with local and global connections in VOICE magazine. You can watch our webinar here.

As an anti-colonial educator, I am actively learning how to centre Indigenous perspectives, knowledge, worldviews, and stories of resistance throughout my curriculum. This integrated water inquiry is one example of what eco-justice pedagogy might look like in Grade 2.

Land as Pedagogy: Welcoming Circle

As I deepen my understanding about how to support Indigenous sovereignty, and actively disrupt settler colonialism, I am coming to know that some of the most powerful work I can do is to build relationships, make connections, and acknowledge land with respect.

Every morning, we begin our day outside. We take a few deep breaths together and pay attention to the land (which includes plants, wind, animals, water, soil, etc.) around us. We notice the clouds, the mist, the frozen puddles, and share our observations with each other. We honour the original caretakers of land, practice gratitude, and promise to care for the land as part of our responsibility as treaty people.

My approach to land education is to honour, celebrate and strengthen the relationships that children have with their natural environment, which includes the urban setting. Inquiry-based learning that is grounded in love and wonder can support children to be curious and critical thinkers. If children feel a strong connection to the land, they might also feel responsible for taking care of the land, and each other.

Building Relationships: Sharing our Water Stories

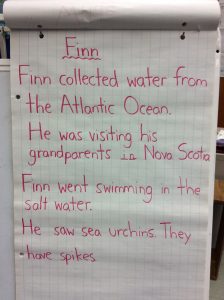

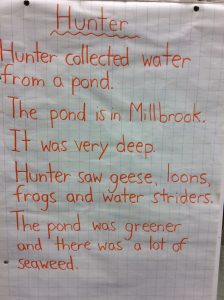

Our water justice inquiry began with an idea that I learned about in the first edition of Natural Curiosity. In September, students shared samples of water that they had collected from different water sources they encountered during the summer. Every day, one student shared what they love about water, and told stories about the water they had collected. We wrote about every experience. This act of storytelling helped to connect us as a community, and created a shared intention for learning with and from water.

A Community of Co-Learners:

Students shared their knowledge and what they love about water in different ways. During MSI (Math-Science Investigations), I asked everyone to build and create structures that connect to water. We used inquiry cards to document what students already knew and the questions they wanted to explore together. These questions provided diagnostic assessment, and will guide our inquiry throughout the year.

Taking Action:

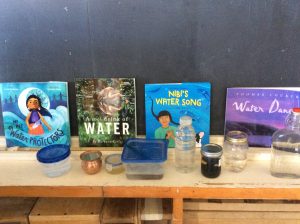

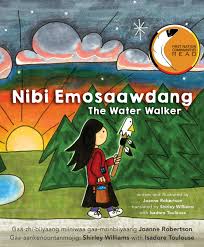

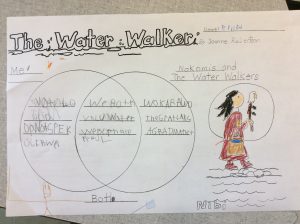

It is critical that young children learn stories of resistance, and see themselves as agents of change. We are reading many picture books to support and guide our inquiry. “The Water Walker” by Joanne Robertson and “Nibi’s Water Song” by Sunshine Tenasco, are two excellent stories written by Indigenous authors. Reading these stories inspired more questions:

Why does Water need to be protected?

Do all people have access to clean water? Why or why not?

How can I take action to protect water?

Students used a Venn Diagram to make text-to-self connections and compare themselves to Anishinaabe Water Protector, Josephine Mandamin.

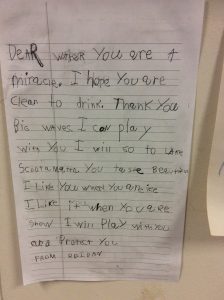

Write for Rights:

As students learn to recognize inequity and confront injustice in their lives, they need multiple strategies and tools that they can use to take action and feel empowered as activists and allies.

Every year, Amnesty International organizes a letter writing campaign on December 10, called “Write for Rights”. In 2020, I learned that Amnesty International was highlighting the First Nations community of Grassy Narrows. I decided that the students would learn about the issues and write letters of solidarity. Everyone was very surprised when Premier Doug Ford wrote us back!

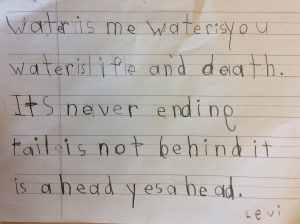

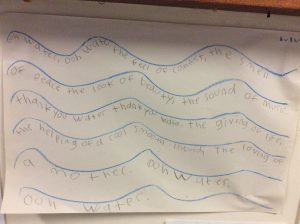

Learning Through the Arts: Water Poems

We are learning that Water Protectors will often sing to the water. This call to action has inspired us to write our own songs of gratitude for water in our local community. In preparation, the Grade 2 students wrote a variety of poems, and we explored the sounds and shapes that water makes through soundscapes and movement. Students expressed their appreciation and love for water in creative ways.

Water Songs:

As we compose our water songs, we will continue to listen to the songs of Water Protectors for inspiration and guidance. Some of the songs that we have been learning are: “The Water Song” by Irene Wawatie Jerome, “Home To Me” N’we Jinan Artist from Grassy Narrows First Nation and “We Stand” by One Tribe (Kelli Love, Jordan Walker, and MC Preach). It is my hope that we will sing our songs to the water, with gratitude and joy.